About the research

The purpose of this research was to estimate the impact of the introduction of the National Living Wage (NLW) in April 2016, and its successive upratings (in 2017 and 2018), on employment retention and hours worked.

The main focus was on how the introduction and upratings of the NLW affected employees aged 25 or over, but the research also looked at differences in impact for this group compared to younger employees. It also explored variations in impact between men and women and part-time and full-time employees, as well as differences by other characteristics, such as the nature of the employer or employment contract.

Research funding and partners

The research was commissioned by the Low Pay Commission (LPC), which is an independent body that advises the Government about the National Living Wage and the National Minimum Wage. The LPC submits a report to the Government each year making recommendations on the future level of the National Living Wage and National Minimum Wage, and related matters.

In making their recommendations, Commissioners take account of the current state of the economy, its future prospects, evidence from stakeholders, and the findings of the commissioned research projects. The research findings are a fundamental part of the decision-making process. The findings are presented to Commissioners (along with academics, government analysts and policymakers) at an annual research symposium. The key findings are then presented by the Secretariat at the Rates-setting Retreat, where the recommendations on future minimum wage rates are agreed. Those findings are integral to decision-making and are summarised in the annual report that sets out the evidence behind the recommendations. The research reports are then published at the same time as the annual report.

Methodology

A difference-in-differences (DiD) analysis was used to explore the impact of the introduction of the NLW in 2016 and upratings in 2017 and 2018 on employment retention and basic weekly working hours for part-time and full-time employees of either gender. The research explored the sensitivity of the findings to changes of specification, including using different comparison groups, and to the inclusion or exclusion of control variables. It also assessed whether impacts varied depending on whether the employing organisation was in the public or private sector, by firm size and whether the employee had a permanent, temporary, or casual contract.

A difference-in-difference-in-differences (DDD) analysis was also used to assess whether the main findings of the research are corroborated when using a different approach to the analysis. This part of the analysis exploited the fact that minimum wage rates diverged for those aged 21 to 24 and those aged 25 or over following the introduction of the NLW in April 2016. This also made it possible to assess whether the impact of the NLW on employment retention and hours varied for employees on either side of the age threshold.

Minimum detectable effects (MDEs) were reported to provide an insight into the magnitude of effects that may be missed when focusing on statistically significant results alone. Elasticities were also reported to indicate the economic significance of the results. These show the percentage change in the main outcomes in response to a 1 per cent increase in the NLW.

Data used from the UK Data Service collection

The data sources for the analysis were the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), covering the period from 2011 to 2018, and the longitudinal Labour Force Survey (LFS). The analysis of the longitudinal LFS explored the impact of the annual upratings of the minimum wage between the October to December quarter of 2010 and the January to March quarter of 2018.

ASHE is based on a 1 per cent sample of payroll records and is therefore likely to provide more accurate data on pay than the LFS. It also benefits from larger sample sizes which mean it is more likely to be possible to detect any impacts and is therefore better-suited to analyses of subgroups within this population than the LFS. However, the LFS has more detailed information on employee and employer characteristics. The main focus was on the analysis of ASHE, given the greater potential for subgroup analyses and to detect statistically significant impacts.

Findings

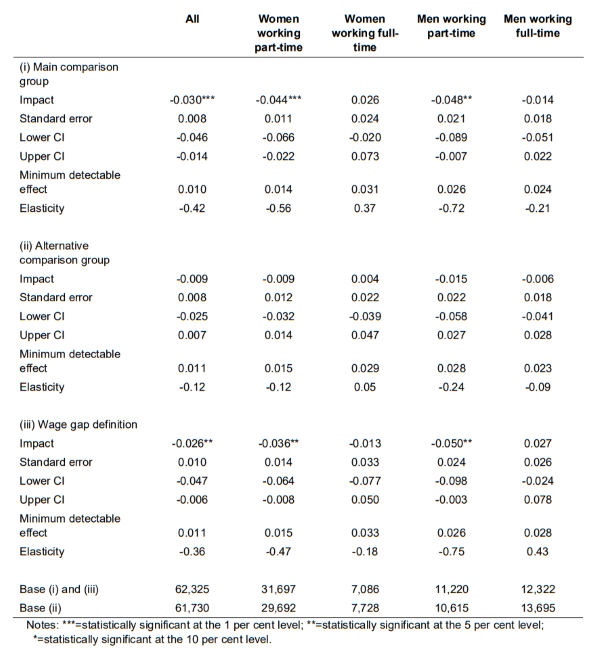

The analysis found that the introduction of the NLW in April 2016 reduced employment retention for both male and female part-time employees (shown in Table 1 below). The finding for women was consistent with earlier analyses by Aitken et al (2018), but they found no statistically significant impact on employment retention for men working part-time. This divergence is likely to be due to differences in the baseline time periods used in each of the reports.

Table 1 Employment retention following the introduction of the NLW in 2016

Source: Capuano et al. (2019). The impact of the minimum wage on employment and hours. Research Report for the Low Pay Commission.

(Download data in Excel format)

For women working part-time a 1 per cent increase in the NLW at the time of its introduction resulted in a reduction in employment retention of around 0.56 per cent. Women working part-time in the public sector in particular appeared to experience the largest reductions in employment retention following the introduction of the NLW.

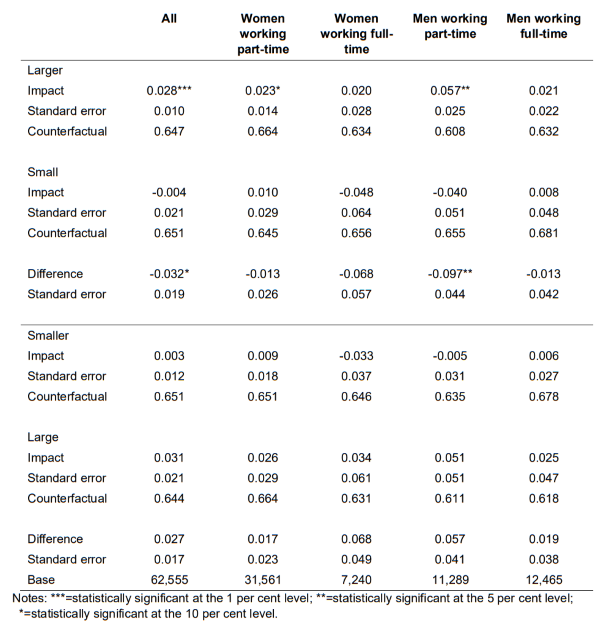

There was little evidence that the 2017 or 2018 upratings affected employment retention for men or women or those on part-time or full-time contracts and the findings for 2017 were consistent with the analysis carried out by Aitken et al. (2018). However, there were signs that the 2018 uprating did have a positive impact on employment retention for women who worked part-time for private sector firms compared to those in the public sector. Also, men who worked part-time for larger firms were more likely to be retained following the 2018 uprating if they worked for a firm with 50 or more employees rather than a smaller organisation (with fewer than 50 employees). This is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Employment retention following uprating of the NLW in 2018, by firm size

Source: Capuano et al. (2019). The impact of the minimum wage on employment and hours. Research Report for the Low Pay Commission.

(Download data in Excel format)

There was little evidence from either ASHE or the longitudinal LFS that the introduction or uprating of the NLW has affected working hours for any of the subgroups of employees by gender or full- or part-time working patterns. Again, this was consistent with the findings of Aitken et al. (2018). There was some evidence from the longitudinal LFS that men who worked full-time experienced a reduction in working hours following the introduction of the NLW in 2016, but this was not apparent in the analysis of ASHE, where larger sample sizes were available.

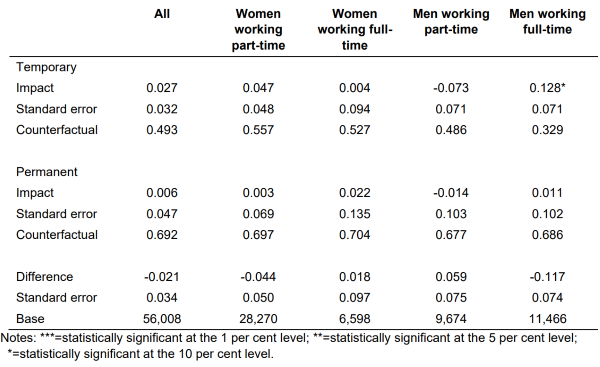

Table 3 shows that men who worked full-time who were employed on a temporary contract experienced an increase in hours following the 2017 uprating of the NLW relative to those who were on permanent contracts. However, there was little evidence to suggest that any of the other characteristics considered had a bearing on the impact of the uprating of the NLW on working hours.

Table 3 Employment retention following uprating of NLW in 2017, by contract type

Source: Capuano et al. (2019). The impact of the minimum wage on employment and hours. Research Report for the Low Pay Commission.

(Download data in Excel format)

Findings for policy

The findings suggest that since the introduction of the NLW in 2016, upratings have had a limited impact on employment retention and working hours for directly affected employees. This is likely to be partly due to the fact that these upratings have been more modest in terms of their effect on real wage growth than the 2016 uprating.

The fact that the larger increase for employees aged 25 or more did result in a reduction in employment retention for part-time employees (and most clearly for women who worked part-time) suggests that caution should be exercised in considering any future rises of a similar magnitude.

Impact

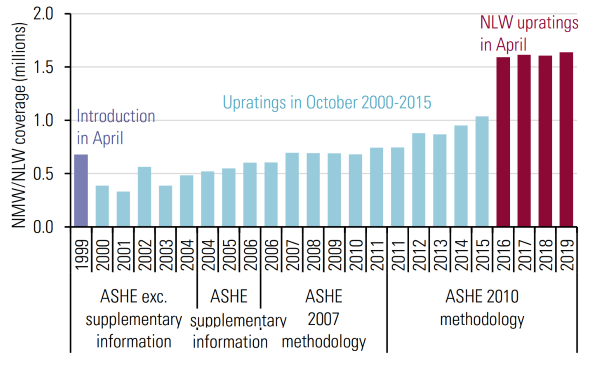

The number of people paid up to 5 pence above the NLW has stood at around 1.6 million since 2016, up from around 1 million in 2015, prior to its introduction. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Coverage of the NMW/NLW for workers aged 25 and over, UK, 1999-2019

Source: Low Pay Commission report 2019 – Summary of findings

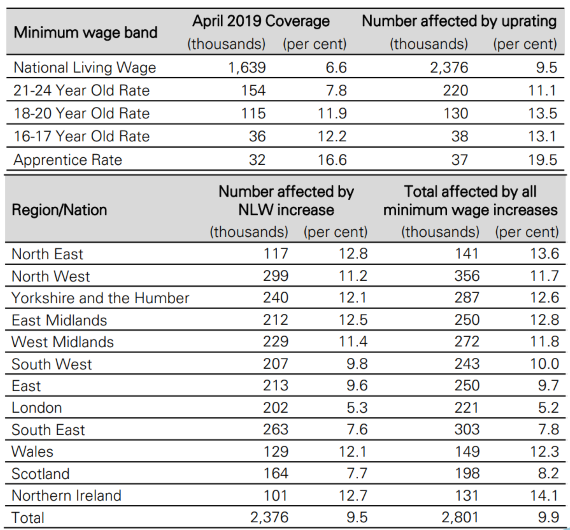

At the time of writing their 2019 annual report, the LPC anticipated that the recommended rates for 2020 would increase pay in around 2.8 million (around one-in-ten) jobs. This is the number of jobs where pay would have to rise in order to stay above the change in the pay floor due to take effect on 1 April 2020. The impact of the wage rise was expected to vary by region with 14% of workers in Northern Ireland and the North East likely to benefit from the increase in the minimum wages, compared to just over 5% in London. Table 4 below shows the coverage of the minimum wage and the number of people who were anticipated to be affected by the increase in the minimum wage uprating in April 2020.

Table 4 Impact of the April 2020 uprating by minimum wage band and by region/nation

Source: Low Pay Commission report 2019 – Summary of findings.

(Download data in Excel format)

Publications

The report

The impact of the minimum wage on employment and hours – IES report for the Low Pay Commission

Related outputs

Blog post for UK Data Service Data Impact blog: ‘A day in the life’: presenting to the Low Pay Commission

Low Pay Commission’s 2019 Report on the National Minimum Wage (NMW) and National Living Wage (NLW)

Research commissioned to inform the Low Pay Commission’s work and recommendations in 2019

Low Pay Commission 2019 summary of findings

The National Living Wage Beyond 2020

News articles related to the National Living Wage

National living wage to rise by 6.2% in April, BBC News website, 31 December 2019

UK minimum wage to rise by four times rate of inflation, The Guardian, 31 December 2019