About the research

Public opinion on climate change is a critical factor in shaping effective climate policy. As governments, researchers and lobbyists increasingly rely on survey data to justify climate action – or inaction – the diversity and complexity of public attitudes, ranging from beliefs and concerns to policy preferences, demand more nuanced and structured analysis.

John Kenny and his research team respond to this challenge by developing a comprehensive classification system for climate-related survey questions. Drawing on over 315 surveys from around the world, including from the UK Data Service, the authors offer a thematic framework that helps researchers and policymakers better understand what is being measured when we talk about “climate change public opinion”.

Why?

Why is this research important?

Climate change is a politically contested issue, and public opinion is frequently cited to justify policy decisions. Yet, until now, there has been no up-to-date, comprehensive framework to classify and interpret the diverse survey questions used to measure climate-related attitudes.

The results of this study reveal that public opinions on climate change are made up of multiple, interrelated components – such as belief, concern, and policy support. These should not be treated as interchangeable and have direct implications for how policymakers interpret survey data and justify interventions.

This study underscores the importance of precise language and framing in climate opinion surveys, cautioning against the aggregation of diverse question types without clear theoretical justification and calling for more context-specific policy support measures in survey design.

The resulting framework is now being used by major European research infrastructures to design climate-focused survey modules. Its adoption across projects like Infra4NextGen and SoGreen demonstrates its value as a tool for generating data on public attitudes towards climate.

Why was this research needed?

As climate change becomes an increasingly urgent and politically charged issue, researchers and policymakers rely heavily on survey data to understand public attitudes and justify action. Yet, the diversity of concepts measured in these surveys – and the context within which they are collected – often leads to inconsistent interpretations and fragmented evidence.

What may appear as contradictory findings may result from different types of climate change questions being used interchangeably and/or inconsistently across or within country and time contexts.

Without a consistent and transparent approach to designing and analysing climate opinion surveys, it becomes difficult for policymakers to draw meaningful conclusions, and for the public to engage with the findings in a clear and informed way.

This work was needed to bring structure and clarity to a rapidly growing field. By offering a comprehensive framework for classifying climate-related survey questions, the study enables researchers to be more precise in what they measure and claim – ultimately helping to ensure that climate policy is informed by robust, interpretable, and socially relevant data.

[U]ncertainties in how publics stand on climate change can make it difficult for political representatives to fulfil their responsiveness function (Chen et al. 2021, p.35).

How?

How was the research carried out?

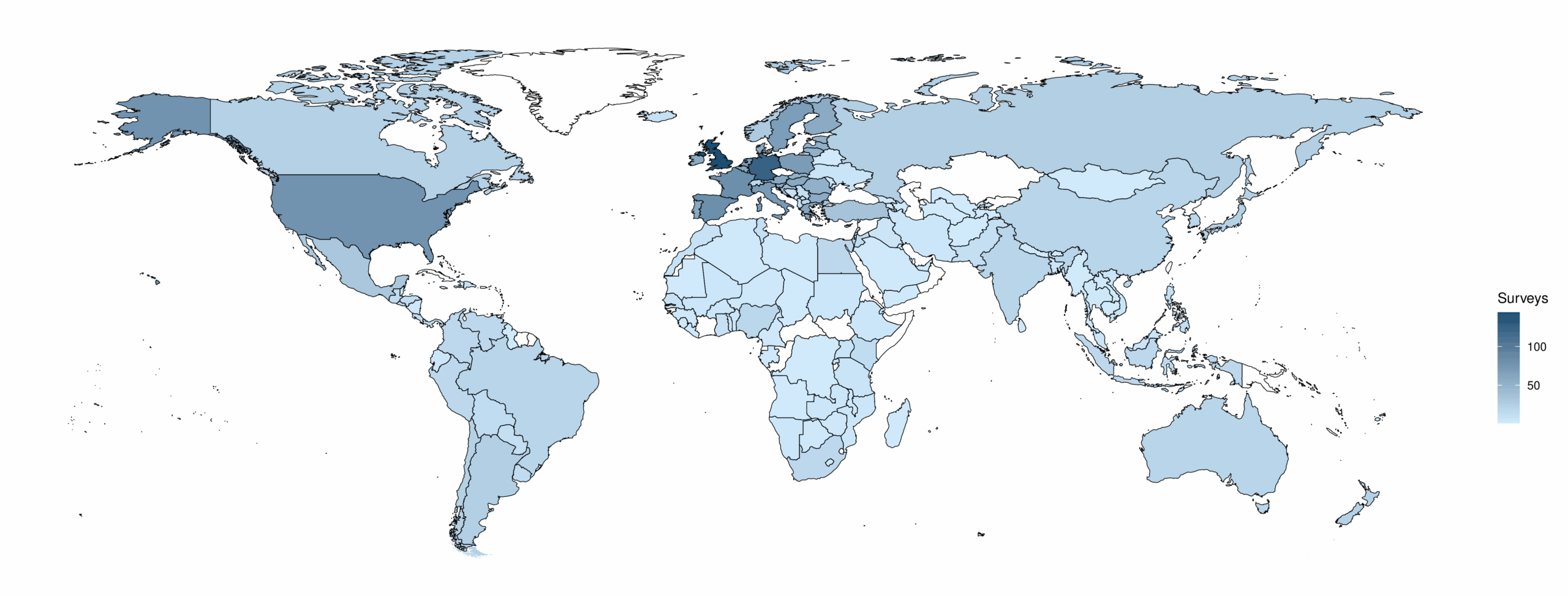

A thorough search was carried out on datasets held by both the UK Data Service and the GESIS repository for surveys containing “global warming” and “climate change”. This approach significantly expanded the geographic scope compared to previous research, with Figure 1 illustrating the globally distributed sample of 315 surveys.

Figure 1: Summary of geographic areas covered by the questionnaire corpus.

Note: The United Kingdom numbers include some surveys of England, Scotland and Wales (taken from Kenny et al., 2024). Larger image / Accessible version.

Qualitative analysis of the language used in these surveys identified key categories of question, which formed the basis of the framework. These categories are given in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of the categories within the classification framework.

| Category | |

|---|---|

| (1) | Information: Engagement, knowledge and sources |

| (2) | Beliefs |

| (3) | Threat; Worry and Concern |

| (4) | Responsibility and Action |

| (5) | Climate Change and the Economy |

| (6) | Public Support for Climate Policies |

| (7) | Evaluation of Action; Representation; and Activism |

How did data held by the UK Data Service help?

The UK Data Service was instrumental in the development of this framework. By providing access to both large-scale national surveys and smaller, specialised datasets, the UK Data Service allowed the research team to build a comprehensive and globally relevant classification system for climate opinion questions.

Large-scale national surveys accessed via the UK Data Service:

- Understanding Society

- British Social Attitudes Survey (waves 2005-2019)

- Office for National Statistics Omnibus Survey (2005-2007)

- Office for National Statistics Opinions Survey (2008-2011)

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: Survey of Public Attitudes to Quality of Life and the Environment (2001)

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: Survey of Public Attitudes and Behaviours toward the Environment (2007 and 2009)

- National Survey for Wales (2018-2019 and 2020-2021)

- Lloyd’s Register Foundation World Risk Poll

Smaller, thematic surveys accessed via the UK Data Service:

- Household survey of climate change perception and adaptation strategies of smallholder coffee and basic grain farmers in Central America

- The 2013/14 winter floods and policy change: Interviews and survey data

- Beyond Nimbyism: a Multidisciplinary Investigation of Public Engagement with Renewable Energy Technologies

- UEA-MORI Risk Survey

- UEA-MORI Genetically-modified (GM) Food Survey

- Public Perceptions of Climate Change and Energy Futures in Britain, 2010

- Public perceptions of climate change and personal experience of flooding

- Perceptions of electricity use at home and in the workplace

- Hampshire Residents and Climate Change, 2003

- Social Influence and Disruptive Low Carbon Innovations

The national surveys offered consistency and longitudinal depth, whilst the smaller studies added nuance and geographic diversity – capturing localised experiences and specific policy contexts.

Importantly, this study demonstrates how the UK Data Service supports not just access, but data discovery – both the Data Catalogue and ReShare repository helped researchers identify relevant surveys they may not have initially considered.

This is particularly valuable in a field like climate opinion research, where the responses to certain framing and wording of questions can vary geographically and culturally.

Access to the data was important in enabling a more comprehensive and representative analysis of climate change opinion surveys, showcasing the UK Data Service as not only a repository for large-scale longitudinal studies but also as a gateway to smaller, geographically diverse and thematically rich surveys that might otherwise remain outside the scope of large analyses. As John Kenny puts it:

This work wouldn’t have been possible without the UK Data Service

How did the researchers do something new?

This research responds to a long-standing challenge in climate public opinion studies: the lack of a comprehensive, up-to-date guide to the types of survey questions used to measure public attitudes toward climate change.

Earlier efforts laid important groundwork by highlighting the need for careful measurement and outlining categorisations; however, these initial categorisations have not kept pace with the rapid expansion of climate policy and scholarship, the evolving political and social landscape, and the growing diversity of survey instruments.

By systematically reviewing 315 surveys and categorising their questions, this study offers a new tool for improving construct validity, guiding future survey design, and supporting more meaningful comparisons across time and geography.

As Roser-Renouf and Nisbet warned, weak measurement can amplify uncertainty and slow progress toward climate solutions. This framework helps mitigate that risk.

What?

What did the researchers find?

As the framework was being developed, the research team linked question categories (listed in Table 1) to the issues they aim to measure, survey responses, and key empirical findings from existing literature. The findings from this analysis are summarised below and form the basis of the recommendations in the next section.

Information: Engagement, knowledge and sources

Survey responses and the literature showed that confidence in climate knowledge didn’t always reflect accuracy, as some people feel well-informed yet what they perceive to be true may contradict scientific understandings. The authors highlighted a possible connection between this finding and:

- organised disinformation efforts by actors with a vested interest in fossil fuels

- bias induced by the equal weighting of scientific consensus and scepticism in the media.

The authors suggest that the design and format of climate survey questions can help address this issue. For instance, by combining self-assessed and objective measures – such as true/false questions on scientific facts – and including questions that explore public trust in actors such as scientists, politicians or the media, a more nuanced understanding of climate knowledge can be determined.

Beliefs

Beliefs about climate change are shaped by personal experiences, media exposure and political messaging. As such, beliefs reflected in survey responses and the literature may sometimes be more fixed and other times more transient. Moreover, there is limited consensus in the literature regarding the role of these beliefs and the perceived lived experiences of climate change such as extreme weather events.

One contributing factor to this identified in the analysis is the format of survey questions; for example, using agree/disagree statements versus categorical scales can significantly influence how beliefs are expressed and interpreted. To further improve clarity, survey designers could focus on longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional surveys that track confidence, opinion strength, and changes in views over time.

Although belief questions are already common in climate surveys, the authors stated the value of carefully designed follow-up questions – particularly on those exploring beliefs about the anthropogenic cause of climate change and how these beliefs have evolved over time. These additions can offer deeper insights into public beliefs and perceptions.

Threat; Worry and Concern

The responses to questions about perceived threats from climate change are multifaceted. The authors identified that people are less likely to view climate change as a threat when:

- their local region experiences (perceived) net benefits from a changing climate, or

- the perceived impacts are seen as distant or far in the future.

The analysis also highlighted the complex relationship between belief and worry, which can be closely tied to the aspects of climate change that are politicised in a given region. For example, within Europe, survey responses show that “worry about climate change is more politicized among individuals than belief in its anthropogenic cause.”

This complexity prompted the authors to warn against merging questions from different categories, as doing so may obscure these important nuances and empirical distinctions.

Responsibility and Action

The literature highlights a recurring issue in climate surveys: the tension between collective and individual action, often shaped by misconceptions about which behaviours are most impactful. For example, one study cited by the authors found that individuals tend to “underestimate high-impact actions such as becoming vegetarian and taking flights, and overestimate lower-impact actions such as avoiding excess packaging”. The analysis found a reflection of this bias in survey questions, with a greater tendency to ask about low-impact behaviours.

Another key issue captured by the authors is the attribution of responsibility – who respondents believe should take the lead on climate action. The analysis revealed question format affects the conclusions made. For instance, asking respondents to choose from a pre-defined list of actors (e.g. government, industry or individuals) does not necessarily reveal how responsible they perceive each actor to be.

The authors argue that surveys that rank or attribute responsibility, and those that measure both collective and self-efficacy, offer clearer insights into how people assign responsibility and expect action.

Climate change and the Economy

Although there is extensive literature on the relationship between climate change and perceptions of the economy, the authors found that the framing of questions in this category can result in varying interpretations on the level of support for climate policy. They identify three different approaches:

1. Framing climate action as being in tension with economic growth, using statements that imply trade-offs; for example, risking jobs or harming the economy

The analysis found that the specifying the extent of the trade-off within the question is key to predicting public support for a policy – some respondents may favour action in principle but withdraw if the perceived cost is too high.

2. Framing climate action itself as economically beneficial or threatening

For example, using questions that elicit the extent to which respondents agree that taking an action would make “companies more competitive” in the market. The analysis found that this approach helps identify respondents who may not act solely to avoid environmental harm but could be persuaded by economic arguments.

3. Presenting climate action as having only positive economic effects, with no trade-offs

The analysis found that these types of questions are more likely to generate supportive responses, as they avoid highlighting potential costs.

Public Support for Climate Policies

Much like the framing of climate-economy questions, the literature shows that public support for climate policies is also shaped by how questions are presented – particularly whether trade-offs are made explicit.

The authors found similar patterns: questions that avoid mentioning costs tend to elicit broader policy support, whilst those that highlight detriments to an individual’s standard of living can reduce it. Additionally, they noted that most policy support questions focus on mitigation rather than adaption. This reflects government priorities and investment patterns; however, as adaptation becomes more central to climate strategies, we can expect survey questions in this area to become more common.

Evaluation of Action; Representation; and Activism

Understanding support for political action and representation is key to understanding electoral dynamics in democratic contexts; however, responses to questions on topics such as whether political parties are doing too much or not enough tend to reflect the political alignment of the respondents.

The authors analysis supports this, with evaluations of current policy varying depending on how questions are framed, which actors are being assessed, and who is being asked. Rather than simply asking which party has the best climate policy, the authors suggest that surveys include ranking issue-position comparisons to assess how closely parties reflect individual views and how this influences voting behaviour or coalition preferences.

A gap between the number of people who have participated in climate activism and those who would consider doing so was also identified in the literature. Based on their analysis, the authors conclude that researchers should explore this gap between participation and willingness to participate by asking about barriers such as lack of information, interest, or perceived efficacy. Additionally, mMeasuring beliefs about the impact of collective action – and clarifying whether respondents prefer to increase or reduce climate efforts – would provide deeper insights.

What do the researchers recommend?

The following data-driven recommendations are particularly timely as climate policy becomes increasingly contested – they reinforce the importance of robust, transparent language in both academic and policy settings.

(1) Researchers should clearly identify which categories of climate change public opinion they are analysing, rather than overgeneralising or merging distinct survey items without a strong rationale.

This will ensure that findings are conceptually sound, contextually relevant, and accurately reflect the diverse influences shaping public attitudes.

(2) Researchers should move beyond an “information deficit” approach when designing questions about belief in or concern about climate change.

There is a pressing need to understand how recognition of climate change translates – or fails to translate – into meaningful beliefs and behaviours that align with scientific consensus. Survey questions need to be designed to ascertain how increased knowledge (or misinformation) translates to beliefs about climate.

(3) Researchers should analyse the relationships between different categories of climate change opinion, rather than treating them as separate or interchangeable.

Understanding how responses within categories interact can reveal important variations in public attitudes and help policy makers tailor more effective communication and policy strategies.

(4) Researchers should design survey questions about climate policy support that are more concrete and context specific.

Abstract or aggregated measures often fail to capture the real-life trade-offs people need to consider, and, as a result, can obscure variation in support for different types of policy instruments across regions and communities.

What was the impact?

The impact of conceptual and methodological research, especially in survey design, is often indirect and difficult to trace. Nevertheless, the influence of this framework is already visible in how climate opinion research is being approached and structured.

Data collection and survey design – early adoption across international contexts

The framework has been adopted by both Infra4NextGen (I4NG) and SoGreen in their survey modules, which have been implemented cross-nationally in the CRONOS-3 panel survey.

Infra4NextGen

The framework for survey questions developed by the research team has been adopted by I4NG to explore young Europeans’ perspectives on climate change and sustainability. It features prominently in their policy-relevant report: European Attitudes to Climate Change and the Environment.

In this data summary, I4NG applies the authors’ framework as an analytical lens to assess existing data from the European Social Survey (ESS), European Values Study (EVS), and the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP). This approach gave them a consistent and standardised method for examining how attitudes vary by age, gender, education level, and place of residence over time.

Coordinated by the European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ESS ERIC), I4NG draws on contributions from several leading social science infrastructures to inform both the NextGenerationEU programme and broader EU youth policy. These include:

- Consortium of European Social Science Data Archives (CESSDA ERIC)

- European Values Study (EVS)

- Generations and Gender Programme (GGP).

In addition to producing data summaries, a key component of I4NG’s work involves selecting questions for the CROss-National Online Survey 3 (CRONOS-3) Panel. This survey represents the first large-scale, cross-national effort to build a panel using consistent methodological principles across all participating countries. CRONOS-3 collects data across eleven countries on themes central to the project:

- Make it Equal

- Make it Digital

- Make it Green

- Make it Healthy

- Make it Strong.

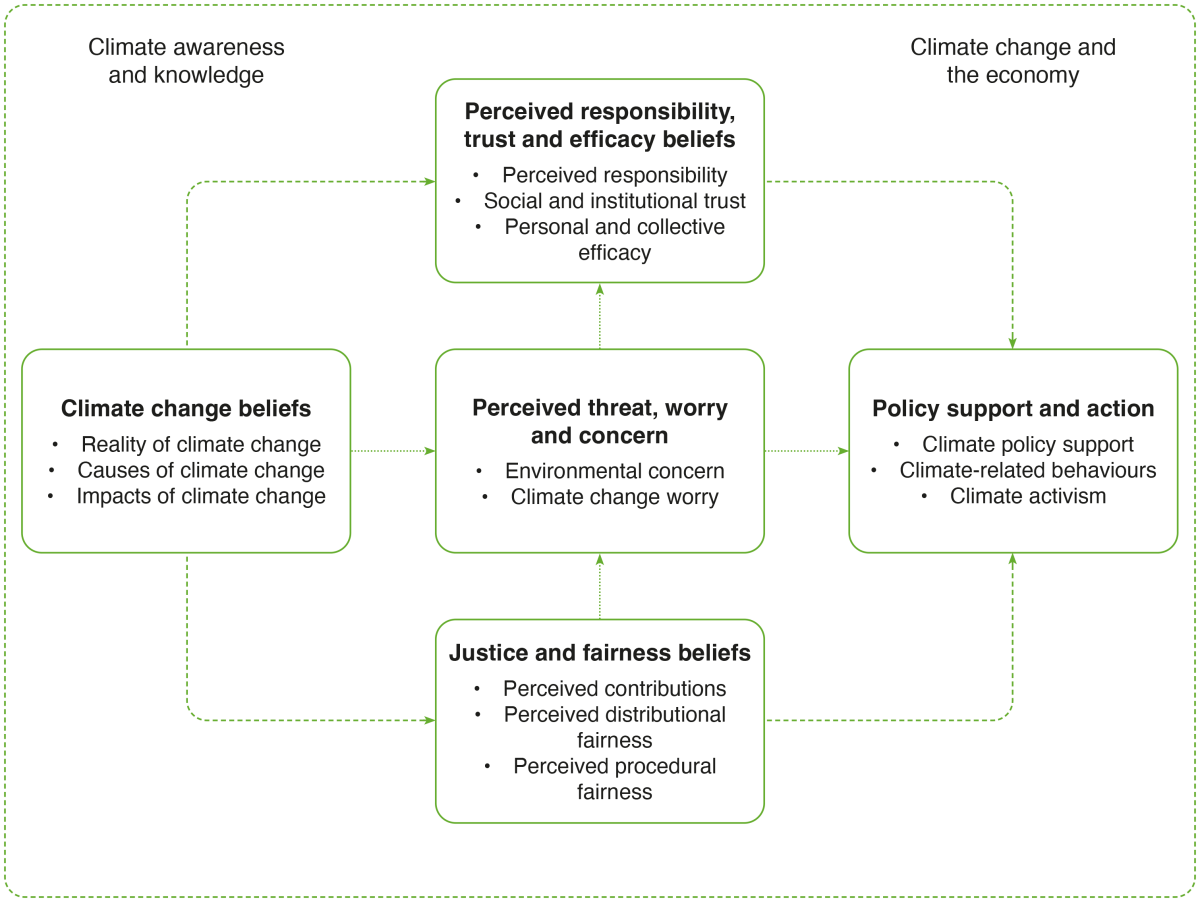

John Kenny’s framework formed the conceptual basis for the Make it Green module of CRONOS-3, which has now been fielded across four waves and is visually outlined in Figure 2. The resulting data – covering youth attitudes toward climate responsibility, energy use, and policy support – is actively shaping EU youth policy and the NextGenerationEU programme.

Figure 2: Conceptual basis for the CRONOS-3 Make it Green module.

Taken from the Infra4NextGen website. Larger image / Accessible version.

Through the ESS Data Portal, insights from the CRONOS-3 Panel are being made available via interactive tools designed to support evidence-based climate action.

The integration of this framework into the Make It Green module of CRONOS-3 ensures that youth attitudes are captured in a way that is both cross-nationally comparable and policy-relevant.

SoGreen

The influence of the author’s framework extends beyond CRONOS-3 into a second major European initiative: the SoGreen project. SoGreen explores the social dimensions of economic transitions driven by climate change by bringing together four leading research infrastructures:

- ESS ERIC

- The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE ERIC)

- The Generations and Gender Programme (GGP)

- Growing Up in Digital Europe (GUIDE).

As part of this work, SoGreen developed a Green Transition Questionnaire module, designed to be embedded within existing longitudinal surveys. It specifically addresses the social consequences of the green transition, which refers to the societal shift towards a more sustainable economy as a means to address the consequences of climate change. It includes questions on job security, energy poverty, and access to transport and infrastructure, reflecting the wide-ranging impact of the green transition on welfare and inequalities.

This Green Transition module is explicitly framed around the conceptual approach developed by John Kenny’s research team, demonstrating the framework’s continued relevance and adaptability across infrastructures.

The Green Transition Questionnaire module, which is distinct from but conceptually aligned with the Make it Green module, was utilised differently by the four research infrastructures:

- ESS implemented the full module in wave six of CRONOS-3 in late 2025.

- SHARE implemented a shorter version of the module across six countries, including Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Sweden and The Netherlands.

- GGP will implement the module in Croatia and Poland as part of the in-between wave surveys.

- GUIDE will implement a revised version appropriate for children and teenagers.

By applying the framework to longitudinal survey instruments that target people at different stages of life, the SoGreen project will enable the collection of harmonised and cross-national data on how different generations and social groups perceive and respond to environmental change.

This coordinated rollout across different projects demonstrates the framework’s versatility and relevance across a broad spectrum of social science research. The UK Data Service has played a key role in enabling the future impact of these survey instruments by providing access to the datasets and documentation that underpin the framework’s development.

Research and academic use – a foundation for future studies

Several peer-reviewed studies have cited the framework whilst exploring public attitudes toward climate risk, political engagement, and environmental policy.

Recent studies include research on:

- Climate risk perceptions and government responses in China

- The relationship between political orientation and opinions on climate change

- Environmental attitudes amongst parents

- Framing climate policies and influencing public opinion.

Additionally, John Kenny was recently (May 2025) invited to the University of Bologna to deliver a seminar on this research.

These citations and invitations demonstrate the framework’s growing traction in academic research and its relevance across disciplines and geographies.

What is next for the researchers?

The researchers drew upon their framework to design original public opinion surveys on climate change that were fielded in Britain, Canada, Chile, Germany and South Africa. The findings from these are currently being analysed and will be published in as part of an Oxford University Press monograph that they are writing.

Additional information

Authors involved in this research

- John Kenny*

- Lucas Geese*

- Andrew Jordan*

- Irene Lorenzoni*

*Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, School of Environmental Sciences, Norwich Research Park, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

Publications

Kenny, J., Geese, L., Jordan, A., & Lorenzoni, I. (2024). A framework for classifying climate change questions used in public opinion surveys. Environmental Politics, 34(6), 1114–1140. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2024.2429264.

Kenny J. and Geese, L. (2025). Publics and UK parliamentarians underestimate the urgency of peaking global greenhouse gas emissions. Communications Earth & Environment. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02655-w.

Research funding and partners

The work was supported by the European Research Council (via the DeepDCarbAdvanced Grant 882601) and the UK Economic and Social Research Council (via the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations (CAST) ES/S012257/1).