About the research

The UK is an urbanised, densely populated country, yet a significant minority of people reside in its rural areas. Living away from major conurbations presents unique challenges, particularly for employment, transport, affordable housing and access to education. Rural labour markets tend to offer a narrower range of jobs, relatively low wages, and difficulties around transport and accessibility. Furthermore, as the rural population is ageing, services and support are targeted at older people whilst provision for youth becomes increasingly scarce. These factors can make it challenging for young people to find job opportunities. (Commission for Rural Communities, 2012)

Dr Martin Culliney, from the Sheffield Institute of Education, has been investigating the extent to which rural location is a labour market disadvantage for young people. He has been studying this topic since starting his PhD at the University of Birmingham in 2009. His article ‘Going nowhere? Rural youth labour market opportunities and obstacles‘ (2014) initially focused on the opportunities and obstacles for young people in the rural job market. By using the British Household Panel Survey to compare rural and urban youth Dr Culliney found that despite youth unemployment being higher overall in urban areas, living in a rural location brings distinct disadvantages. Most rural jobs are provided by small employers who rely on informal recruitment practices to fill job vacancies, which are often unadvertised. This excludes young people without the right personal contacts. The research also found that many young people aspired to work in specifically rural occupations, even when they understand that this poorly paid or lacks promotion prospects. In another paper, ‘The rural pay penalty: youth earnings and social capital in Britain’, Dr Culliney investigated whether rural location affects the earnings of young people in full-time employment in Britain. He found that rural youth experience a significant ‘pay penalty’ compared to urban peers. Although youth unemployment is higher in urban areas, lower pay and higher housing costs put rural youth at a disadvantage compared to their urban counterparts.

Following on from this, Dr Culliney explored whether rural/urban location impacted on the earnings of young people as they moved into adulthood. The article, ‘Escaping the rural pay penalty: location, migration and the labour market’, demonstrated that young people who remain in rural locations suffer from a ‘pay penalty’ of lower earnings and slower wage growth compared to those who relocate to urban areas. Individuals starting their working life in urban areas before moving to the countryside earned considerably more than those who had stayed in a rural area throughout the entire study (1991-2008/9). In 2008/9 people who had moved from urban to rural locations reported median net earnings of £23,400 per year, whilst their contemporaries who stayed in rural areas earned just £14,400. This difference in salary is attributed to the limited job options in rural areas, the relative absence of large employers, and the prevalence of low-skilled work. The earnings of young people who moved from the countryside to towns or cities did rise but at a slower rate than for other groups.

Methodology

Dr Culliney’s work on the rural labour market uses a combination of data from the British Household Panel Survey and fieldwork data collected during the course of his doctoral research.

The analysis in ‘Escaping the rural pay penalty: location, migration and the labour market’ used data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). It followed members of the 1991 ‘youth cohort’, who were aged under-25 in the first wave of the survey, as they progressed into adulthood. This approach sought to exploit the longitudinal structure of BHPS by tracking respondents for the full 18 year observation period. Taking this long view of labour market outcomes generated insights into employment careers from youth into adulthood, with original sample members in their late thirties or early forties by the final wave of the survey.

Rural/urban areas were classified according to the ONS definition, wherein settlements of 10,000 or more inhabitants are deemed to be urban. Geographical indicators in the BHPS are only available as a conditional access extension file. This was merged with the main dataset to perform the analysis, the first time that a longitudinal comparison of urban and rural youth earnings in Britain has been carried out.

Linear mixed models were used to gauge the effect of rural/urban origin and current location on earnings over time. This approach was adopted for the flexibility to incorporate both time-invariant (rural/urban origin) and time-varying (rural/urban location) predictors into a model with a continuous outcome (earnings). Earnings were adjusted for inflation to ensure robustness of the comparisons over time and individuals reporting no pay were excluded from the analysis.

Findings and application for policy

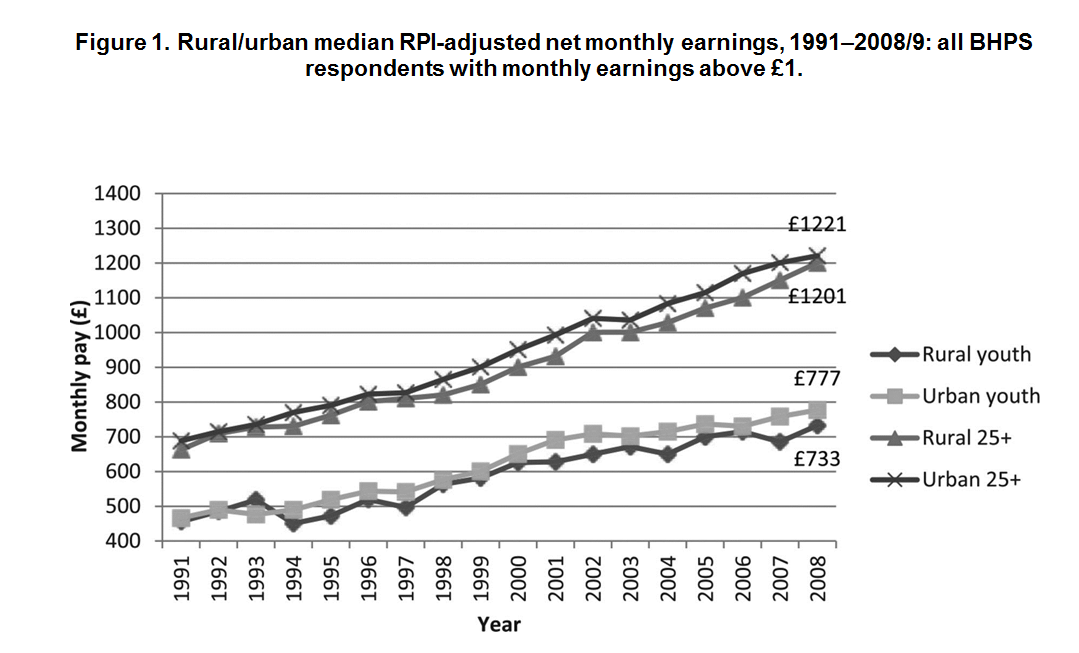

The results showed that although the earnings of people aged 25 were higher in rural areas than urban areas, rural youth earned less than young people in urban locations. This analysis only includes respondents in full-time employment, and is displayed in Figure 1.

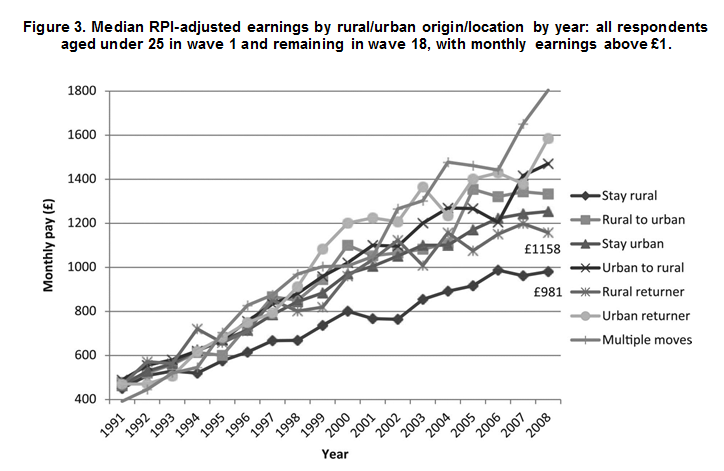

Having considered the level of earnings in different age groups, Dr Culliney used the data to analyse how rural/urban location and migration affected earnings. The research showed that the lowest paid group was those that originated in rural areas and remained rural, but rural-to-urban movers saw their earnings rise faster (as shown in Figure 3). Those relocating from urban to rural areas maintained their higher earnings compared to those who remained rural, suggesting that the rural ‘pay penalty’ results from starting out and staying in a rural location.

For young people living in rural areas, the reduction in their earning power compared to their urban counterparts poses several key challenges for policy makers. Dr Culliney explains,

“If living costs in rural Britain are higher, and youth earnings are lower, what can be done to address this? If young people remaining in rural areas face greater living costs while their earnings increase at a slower pace than other groups, what can be done to ensure that they do not suffer? Less disposable income in rural locations surely acts to the detriment of local services such as shops and pubs, which also perform important social functions in the communities they serve, and are most crucial to those less able to make use of more distant amenities: the poor, the disabled, the elderly and the young. If young people are disadvantaged in the rural labour market, the consequences for rural communities more broadly could be severe, and the disadvantage faced by these marginal groups will be compounded.”

Dr Culliney’s research has been used by the Rural Policy Centre as evidence in the 2014 Rural Scotland in Focus report focusing on how young people can contribute to a vibrant rural Scotland. The report recommends a continued focus on supporting young people’s participation in the labour market. The research was also used in the Scottish Government Review of Equality Evidence in Rural Scotland which found that lack of work opportunities was one of the driving factors for young people leaving rural areas of Scotland.

Publications

Culliney, M (2016) ‘Escaping the rural pay penalty: location, migration and the labour market’, Work, Employment & Society. DOI: 10.1177/0950017016640685

Culliney, M. (2014) ‘The rural pay penalty: youth earnings and social capital in Britain’ Journal of Youth Studies, 17 (2), pp. 148-165. DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2013.793788

Culliney, M. (2014) ‘Going nowhere? Rural youth labour market opportunities and obstacles’, Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 22 (1), pp. 45-58. DOI: 10.1332/175982714X13910760153721