About the research

Laura J Brown, Ph.D student and Dr Rebecca Sear, Head of the Department of Population Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine analysed the Millennium Cohort Study and the Born in Bradford Study to analyse environmental quality and socioeconomic status on incidence of breastfeeding to test whether:

(i) higher local environmental quality predicts a higher likelihood of breastfeeding initiation and longer duration;

(ii) higher socioeconomic status (SES) provides a buffer against the adverse influences of low local environmental quality.

Their research focused on the following questions:

- Are localised measures of environmental quality associated with breastfeeding initiation and duration?

- Does higher socioeconomic status mitigate against negative effects of environmental adversity on breastfeeding?

- Are environmental effects on breastfeeding mediated by birth outcomes?

- Does breastfeeding cluster with other parenting, reproductive and health behaviours to form distinct behavioural strategies?

Life history theory, which aims to predict and explain the observed patterns in life histories of living organisms, such as their timing of maturation and age at first birth, suggests that environmental quality may also pattern maternal investment, including breastfeeding. The research approached infant feeding inequalities among UK populations from an evolutionary perspective, where human behaviour is considered in terms of interactions between genes and environment. The research used two UK cohort datasets to explore the potential role of environmental quality in explaining socioeconomic differentials in breastfeeding; the Millennium Cohort Study and the Born in Bradford Study.

The research formed the basis of Laura Brown’s PhD and examined the local environment in detail, operationalising environmental quality in different ways to understand the role of environmental quality as a driver of socioeconomic status-breastfeeding incidence in the UK. The research found that lower environmental quality was associated with lower odds of initiating and higher risk of stopping, breastfeeding.

Human environments are both social and physical, requiring consideration of a diverse range of environmental quality indicators in order to capture socioecological context sufficiently. Behavioural responses to environmental conditions can be viewed from an adaptationist perspective where different behavioural responses are not necessarily better or worse than one another but reflect different solutions to different constraints and opportunities. Using a human behavioural ecology approach, the research predicted that mothers will reduce breastfeeding, a key indicator of parental investment, in harsh environmental conditions and/or when resources are low, and increase investment when conditions are more favourable.

A human behavioural ecology perspective emphasises the links between people and their environments. Humans do not exist in a vacuum, instead behaviour is shaped by multiple layers of influence. Evolutionary life history theory serves as a useful framework for understanding human reproductive behaviour. It emphasises the importance of environmental quality in predicting behaviours such as parental investment and thereby shifts focus away from individual factors and towards modifiable aspects of the environment.

Funding for the research

Laura’s research was funded by an ESRC +3 Ph.D Studentship from the UCL, Bloomsbury and East London Doctoral Training Partnership.

Key messages:

Socioeconomic status is a stronger predictor of breastfeeding than environmental quality, but the two are strongly linked and each exert independent effects.

The effects of the local environment are complex and dependent upon the indicators of environmental quality used. Associations are not driven by individual environmental perception as much as they are by more objective measures of environmental quality. Less perceivable, more physical measures of environmental quality do not explain the socioeconomic status-breastfeeding association, suggesting that in the UK context at least, sociocultural environmental factors are likely to have an important influence on breastfeeding outcomes.

Breastfeeding, whilst no longer necessary for infant survival in the high-income context of the UK, appears to still be a key aspect of women’s parenting behaviour.

Methodology

Datasets and variables

Two UK datasets were used for the analyses – the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) and the Born in Bradford study (BiB).

The MCS is a nationally-representative ongoing longitudinal study following the lives of around 19,000 children born in the UK between 2000 and 2002 whilst BiB follows the health and wellbeing of over 13,500 children born at the Bradford Royal Infirmary, West Yorkshire, England between March 2007 and December 2010.

As the researchers were interested in women’s infant feeding behaviours and environmental quality, data was used from the first two sweeps of the MCS when the cohort members were 9 months and 3 years old. The BiB data used was from surveys administered up until the cohort members were 4 years old.

Maternal questionnaires and health visitor records were used to derive breastfeeding outcomes, focusing on initiation and duration of any breastfeeding. Environmental information was obtained from maternal questionnaires, independent observer neighbourhood assessments (MCS only), air pollution exposure calculations (BiB only) and routine water chlorination records (BiB only).

Socioeconomic status was measured by job status, educational qualifications, income (MCS only), food security (BiB only), and whether mothers were experiencing financial difficulties or receiving means-tested benefits. Various infant and maternal characteristics known to be important predictors of breastfeeding (e.g. age, ethnicity, birthweight etc.) were also controlled for and the last study included other indicators of parenting, reproductive and health behaviours derived from maternal questionnaires.

Study 1 – Local environmental quality and breastfeeding in the MCS

The study compared objective and subjective summary measures of the local environment using factor analysis to pull together both physical aspects (such as levels of litter, graffiti and building conditions) as well as sociocultural aspects (such as safety, experience of racism, and observations of people arguing or fighting on the street).

Using multi-level modelling on nationally-representative data (the MCS) and controlling for the effects of birthweight, maternal age, partnership status, ethnicity, immigration and acculturation, the effects of the local environment on breastfeeding initiation and duration above and beyond that of individual socioeconomic status (measured as job status, qualification level, and income in different sets of models) and wider-scale deprivation and other ward-level factors such as ethnic composition were isolated to test whether:

1) higher local environmental quality predicted higher likelihood of breastfeeding initiation and longer duration; and

2) higher socioeconomic status provided a buffer against the adverse influences of low environmental quality.

Study 2 – Physical environmental quality and breastfeeding in BiB

The first study provided a UK-wide picture of the relationship between summary measures of environmental quality and breastfeeding and the second study concentrated on one geographical region in particular and focused instead on specific aspects of the physical environment.

Using the BiB dataset, with its largely bi-ethnic Bradford population, the study examined:

1) the influence of the physical environment (measured by water disinfectant by-products, air pollution, passive cigarette smoke, and household condition) alongside socioeconomic indicators on breastfeeding outcomes; and

2) whether there were differences between White British and Pakistani-origin mothers.

Regression models were run separately for each environmental quality indicator and controlled for maternal smoking, cohabitation status, immigration status, BMI, age, parity, the sex of the infant and whether it was a multiple birth and additionally for socioeconomic disadvantage (a summary score derived from mother’s education, her partner’s occupation, financial difficulties, means-tested benefits and food insecurity). Structural equation modelling was used to explore whether environmental quality-breastfeeding associations were mediated by birthweight, gestational age, head circumference or abdominal circumference.

Study 3 – Life history strategies in the MCS and BiB

The third study used both datasets to situate breastfeeding within a wider suite of reproductive, parenting and health behaviours including other parental investment measures, menarche and age at first birth.

Latent class analysis was used to:

1) test whether these characteristics clustered together to form identifiable behavioural strategies; and

2) whether these strategies could be predicted by socioeconomic disadvantage and environmental harshness.

Analyses were restricted to and stratified by the two largest ethnic groups in both samples – White UK born and Pakistani-origin.

Interdisciplinarity

The research draws on literature from a range of disciplines, including demography, anthropology, evolutionary biology and public health. Adopting a human behavioural ecology approach, predictions are derived from the evolutionary framework of life history theory, within which breastfeeding is considered a key indicator of parental investment, and environmental quality and resource access are essential determinants of behaviour.

Data used from the UK Data Service collection

University of London. Institute of Education. Centre for Longitudinal Studies. (2012). Millennium Cohort Study: Second Survey, 2003-2005. [data collection]. 8th Edition. UK Data Service. SN:5350, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5350-3

University of London. Institute of Education. Centre for Longitudinal Studies. (2012). Millennium Cohort Study: First Survey, 2001-2003. [data collection]. 11th Edition. UK Data Service. SN:4683, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-4683-3

Messages

Socioeconomic status is a stronger predictor of breastfeeding than environmental quality, but the two are strongly linked and each exert independent effects.

The effects of the local environment are complex and dependent upon the indicators of environmental quality used. Associations are not driven by individual environmental perception as much as they are by more objective measures of environmental quality. Less perceivable, more physical measures of environmental quality do not explain the socioeconomic status-breastfeeding association, suggesting that in the UK context at least, sociocultural environmental factors are likely to have an important influence on breastfeeding outcomes.

Breastfeeding, whilst no longer necessary for infant survival in the high-income context of the UK, appears to still be a key aspect of women’s parenting behaviour.

Findings

Study 1 – Local environmental quality and breastfeeding in the MCS

Study 1 found that higher objective, but not subjective, local environmental quality predicted higher likelihood of starting and maintaining breastfeeding over and above individual socioeconomic status and area-level measures of environmental quality.

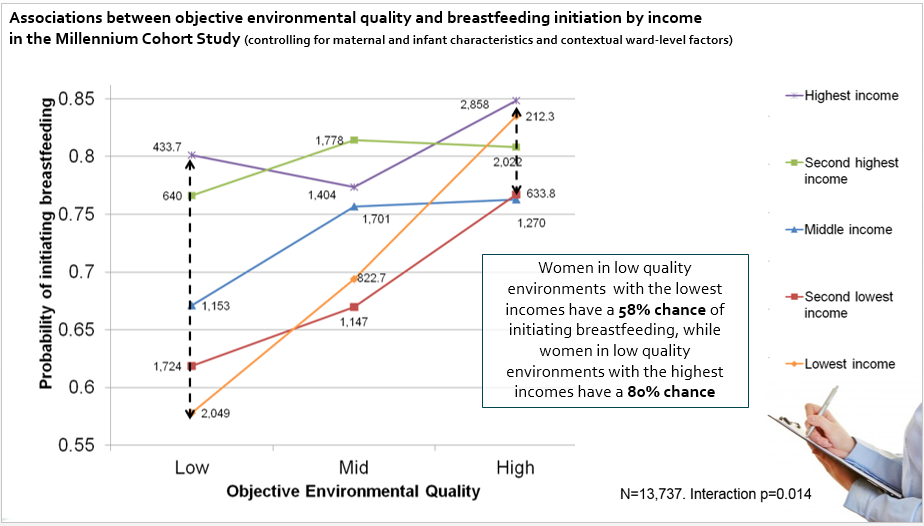

Higher individual socioeconomic status was protective, with women from high-income households having relatively high breastfeeding initiation rates (Figure 1) and those with high status jobs being more likely to maintain breastfeeding (Figure 2), even in poor environmental conditions.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Study 2 – Physical environmental quality and breastfeeding in BiB

Study 2 found the predicted negative association between socioeconomic status and breastfeeding, but no strong or consistent evidence for the same relationship when physical measures of environmental quality were used.

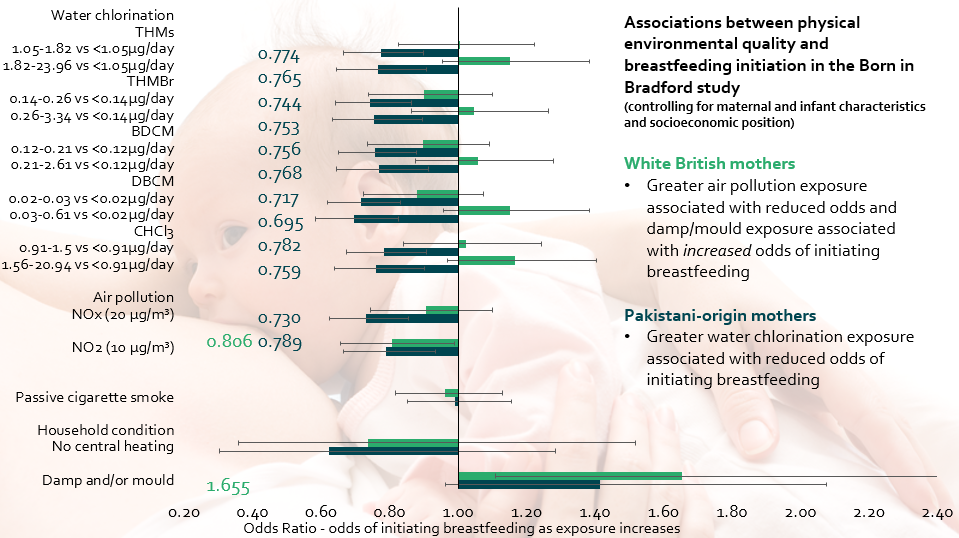

Results of the initiation analyses were broadly in the predicted direction, with greater environmental exposure conferring reduced odds of initiation with the exception of the damp/mould indicator, though not all environmental indicators were significantly associated with initiation and there were some differences between ethnic groups. Pakistani-origin mothers had lower chances of initiation with increased exposure to water chlorination chemicals, but White British mothers were not affected by this exposure (Figure 3).

Results for breastfeeding duration were even more mixed and did not offer strong support for our predictions, and in fact increased air pollution exposure was associated with significantly lower chances of stopping breastfeeding for White British mothers (Figure 4).

Although passive smoke exposure had no direct effect on breastfeeding, the mediation analyses suggested that White British mothers exposed to passive smoke at home or at work had lower birthweight infants who were in turn less likely to be breastfed. Whilst this indirect effect was in the predicted direction, White British mothers with greater air pollution exposure (as indexed by both nitrogen oxides and nitrogen dioxides) was associated with longer gestations and in turn reduced hazards of stopping breastfeeding (i.e. longer durations), which goes against the researchers’ prediction that increased exposure leads to smaller neonates and reduced breastfeeding. These effects were however only significant at the 10% level, and the researchers found no evidence for mediation amongst Pakistani-origin mothers.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Study 3 – Life history strategies in the MCS and BiB

Study 3 found that parenting, reproductive and health traits clustered together to form one of two behavioural strategies i.e. a “fast” or “slow” life history, but only to a limited extent. Breastfeeding was a particularly important discriminating feature, showing clear differences across “fast” and “slow” groups.

Parenting traits clustered together with reproductive traits reasonably well, but health traits did not pattern cohesively. “Fast” life histories were predicted by greater socioeconomic disadvantage and environmental harshness across the four groups of mothers, although some indicators of adverse environments (experiencing parental death, living away from home before age 17 and exposure to air pollution) significantly reduced the chances of adopting a “fast” strategy for some. Pakistani-origin mothers showed less pronounced clustering of traits as well as weaker associations with socioeconomic and environmental characteristics than White-UK born mothers.

Findings for policy

Although the findings of these studies are complex and nuanced there are clear policy implications.

This research suggests that in addition to the breastfeeding-specific barriers highlighted by UNICEF, there are more distant, and sometimes more subtle, influences on women’s behaviour: the barriers behind the barriers. The findings support a shift in focus away from individual factors and towards altering the landscape of women’s decision-making contexts when considering behaviours relevant to public health.

It is now well-known that young White women from deprived areas are the least likely to breastfeed (McAndrew et al., 2012). Brown and Sear’s research has shown some of the ways that this disadvantage is created. The studies have improved upon assessments of area-level deprivation by measuring localised and individualised environmental experiences. Their research has shown that although the ethnic majority, White UK-born women are particularly susceptible to adverse environmental exposures, they are perhaps lacking the sociocultural protection afforded by the cultural and religious affiliations of other ethnic groups.

The research indicates a clear need to improve the support for women to breastfeed in public. Women who are brave enough to breastfeed in public are judged negatively. There is also a need to address the physical aspects of the environment to render it more supportive of healthful infant feeding practices. Addressing this need can take several forms – from clearing the streets of dog mess to rethinking water chemical processes – every step towards making local environments cleaner and safer is a step towards helping mothers and their babies, and likely a step towards improving the health of the rest of the neighbourhood too.

Public Health England sets out four things that need to be done to improve breastfeeding rates (Public Health England & UNICEF UK, 2016):

1) Raise awareness that breastfeeding matters

2) Provide effective professional support to mothers and their families

3) Ensure that mothers have access to support, encouragement and understanding in their community; and

4) Reduce the promotion of formula milks and baby foods.

The research suggests that policymakers can help by:

5) Addressing the broader environmental issues that are patterning reproductive and parenting behaviour

Early life experiences play a key role in shaping health and behaviour, but environmental interventions are not limited to changing childhood exposure. Importantly, Brown and Sear’s research has also shown that changes to adult environments can still make a difference and it is never too late to intervene.

Impact

Laura has presented her

research at several conferences and to a wide range of audiences including the

2017 CLOSER

Health Conference, the 2017 Maternal

and Infant Nutrition and Nurture Unit Conference and the 2018 European

Human Behaviour and Evolution Association Conference.

Publications

Laura J Brown, Rebecca Sear, Local environmental quality positively predicts breastfeeding in the UK’s Millennium Cohort Study, Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, Volume 2017, Issue 1, January 2017, Pages 120–135, https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eox011

Blog post: The UK’s breastfeeding problem: a societal issue with an environmental solution?