About the research

The driving force behind this report came from Efua Dorkenoo, OBE, who was a leading campaigner against Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). Amongst many other things, she was responsible for making the case for new estimates of the prevalence of FGM and for obtaining funding for this work, at a time when limited funds were available for studies of FGM. The report contains estimates of the numbers of women with FGM born in countries where FGM is known to be practised and living in England and Wales in 2011, the numbers of women with FGM born in these countries giving birth and the numbers of girls born to them.

Headline figures for England and Wales were published in an interim report in 2014. The report was published by City University London, as it was then called, in association with Equality Now and funded by the Trust for London and the Home Office. The full report, published in July 2015, contains estimates at Local Authority (LA) level. It also contains data about the extent to which FGM is practised in the women’s countries of origin which were used along with data about the populations of women born in these countries and living in England and Wales in 2011.

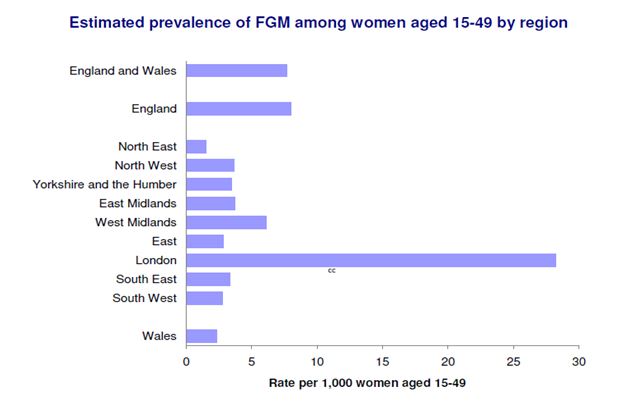

Overall, 433,948 women and girls who were born in countries where FGM is practised were recorded as being permanently resident in England and Wales in the 2011 Census. It was estimated that 137,000 of them had been subjected to FGM, a rate of 4.8 per 1,000. Estimated prevalence rates for all regions and local authority areas in England and Wales showed wide variations. The highest rates of prevalence for women and girls affected by FGM were found in London the region, with Southwark having the highest prevalence rate of 47.4 per 1,000. Although some areas had very low estimated rates, the rate was zero nowhere.

Methodology

Age specific rates of prevalence of FGM were derived from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) undertaken by governments with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), supported by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Both sets of surveys are household interview surveys using a common design and sets of questions to collect data about population, health, HIV, and nutrition. In countries where this is relevant, the surveys have a page of questions asking women whether they and any daughters have been subjected to FGM. Age specific prevalence rates were extracted from summary reports published by UNICEF and DHS and then updated by going to the DHS and MICS web sites to look for reports of any more recent surveys.

To estimate the prevalence of FGM in the population, demographic data about women and born in these countries and girls were derived from the 2011 Census and the numbers in each age and country group were multiplied by the age specific prevalence rates derived from the DHS and MICS surveys to estimate the numbers of women and girls in England and Wales as a whole and in each region and local authority area. It was not possible to estimate numbers of women and girls born in the UK or other countries who had been subjected to FGM. Although most families abandon the practice on migration to the UK and it is illegal, some do not but there are no reliable data on the subject.

A similar approach was used to estimate the numbers of women with FGM living in each local authority area giving birth each year from 2005 to 2013 and the numbers of daughters born to them. The age specific prevalence rates were applied to data from birth registration.

To enable these analyses to be done, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) provided an extract of de-identified Census records of women born in the countries where FGM is practised and de-identified files of data about maternities and live births from records of registrations of births in England and Wales in the years 2005 to 2013. The analyses were done the secure environment of the ONS Secure Research Service (SRS), previously known as the Virtual Microdata Laboratory (VML).

The national data on prevalence in the population and maternities and live births of girls for the years 2005 onwards were combined with data from an earlier project to produce estimates of numbers of women delivering and of girls under 15 born to women with FGM by country group.

Research findings

The key findings of the research were compared with those from the earlier project which used data from the 2001 Census. The main three age groups used in the research findings were 0-14, 15-49, 50 and over. Combining figures represented a prevalence rate of 4.8 per 1,000 women, or an estimated 137,000 women and girls born in countries where FGM is practiced and who were permanently resident in England and Wales in 2011. Additional key findings of women and girls who were permanently resident in England and Wales in 2011 showed that:

- The overall numbers of women aged 15-49 born in FGM practising countries increased from 182,000 in 2001 to 283,000 in 2011

- An estimated 103,000 women aged 15-49 with FGM who were born in FGM practising countries, compared with an estimated 66,000 in 2001. This represented 7.7 women per 1,000 in this age group in 2011

- It was estimated that there were almost 10,000 girls aged 0-14, born in FGM practising countries that had undergone or were likely to have undergone FGM

- In addition there were an estimated 24,000 women aged 50 and over who had been born in FGM practising countries

- Numbers of women born in countries in the Horn of Africa, where FGM is almost universal and where the most severe Type lll form of FGM is common, and who were resident in England and Wales, increased by 32,000 from 22,000 in 2001 to 56,000 in 2011

Estimated prevalence rates varied widely by region and FGM tended to be more prevalent in urban areas. London had by far the highest regional rate at 21.0 per 1,000 women and girls. In addition, the highest prevalence rates were in London boroughs, with an estimated 47.4 per 1,000 in Southwark and 38.9 per 1,000 in Brent.

Outside of London, the highest prevalence rates, ranging from 12 to 16 per 1,000 women and girls, were found in Manchester, Slough, Bristol, Leicester and Birmingham. Other authorities, including Milton Keynes, Cardiff, Coventry, Sheffield, Reading, Thurrock, Northampton and Oxford had rates of over 7 per 1,000. In contrast, many mainly rural areas had prevalence’s well below one per 1,000, but above zero, so there was no LA that was unaffected by FGM.

It was estimated that since 2008, women with FGM made up about 1.5 per cent of women giving birth in England and Wales each year and about three fifths of them were born in the countries of the Horn of Africa where FGM is almost universal and the severest form, Type III is widely practised. The percentages of girls who were born to mothers with FGM ranged from 10.4 per cent in Southwark to under 0.1 per cent in many other local authorities.

The figures found in the report might be slight underestimates as they do not take account of further migration since 2011. In addition, many women who migrated from countries where FGM is practised report their ethnicity as Black African and there was under-enumeration of Black African women in the Census compared with the population of England and Wales as a whole. On the other hand, a relatively high proportion of women in the 15-49 age group were graduates and in some countries more highly educated women are less likely than others to be subjected to FGM than others. In addition, there are differences between populations within countries in the extent to which they practice FGM, but data about these countries are not subdivided into regions in census and birth registration data.

Impact of the research and findings for policy

The estimates were needed to plan services for affected women, both to provide appropriate maternity care and to provide care for the consequences of FGM as they grow older. They were also used to inform child protection services for their daughters. Estimated numbers of women with FGM and numbers of girls born to them were disseminated to LAs and also to other relevant organisations to produce guidance and support their community safety role in the reduction of FGM.

Informed by the data collected, in collaboration with the Trust for London, Rosa the UK Fund for Women and Girls, the Royal College of Midwives and City University London, Equality Now sent a guide to all local authorities, helping them to understand the data and to give guidance on the types of action required with some good practice examples, including how to make best use of existing resources. It also provided links to existing resources for easy reference and the latest information from expert groups.

Section 74 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 imposes a mandatory reporting duty on people who work in a “regulated profession” in England and Wales to notify police of known cases of FGM. Section 11 of the Children Act 2004 places a duty on all professionals “to safeguard and promote the welfare of children” and as such, all professionals have a duty to protect children from FGM. Data on prevalence of FGM is therefore useful in identifying the scope of FGM in order to prevent it, but also importantly to identify where women and girls need help and support to deal with any physical or psychological consequences of FGM.

The report shows the estimated numbers of women with FGM have increased since 2001, especially due to migration from countries in conflict. A substantial proportion of the increase is due to women from countries where FGM is nearly universal or prevalence is high, who migrated between 2001 and 2011. What the data showed was that while many affected women live in large cities where migrant populations tend to be clustered, others are scattered in rural areas. No local authority area is likely to be free from FGM entirely. In many areas, the estimated prevalence is low, but there are still some women who may be affected by FGM. This is important information to underscore that action needs to be taken by each local authority. When planning services to meet the needs of women with FGM and assessing whether there is a need for child protection for their daughters, it is important to recognise the diversity of the ethnicities of the women discussed in the report, and to assess their needs at an individual level. While dedicated services may be needed in areas with large numbers of women with FGM, services in all areas should be aware of their needs and have strategies to meet them.

Read the Report

Related publications and outputs

A Tribute to Efua Dorkenoo

frontlinewomensfund.org/2024/10/no-title/