About the research

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) has a statutory duty under the Equality Act 2006 to report to the UK Parliament on how far everyone in Britain is able to live free from discrimination and abuses of their human rights. ‘Is Britain Fairer? 2018’ is the most comprehensive review of how we are performing on equality and human rights. Looking across all areas of life, including education, work, living standards, health, justice and security, and participation in society, the report provides a picture of people’s life chances in Britain today.

Methodology

The EHRC has developed a Measurement Framework to collect and analyse the most robust and relevant evidence, to monitor progress in a consistent way and to measure change over time. The Measurement Framework is made up of a series of indicators to “assess the elements of life that are important to all of us”, including being healthy, getting a good education, and having an adequate standard of living.

The researchers looked at specific topics within each indicator, such as bullying at school, domestic violence and life expectancy. For each topic they gathered information on law, policy and people’s lived experiences. They used a range of qualitative and quantitative data, and breaking down the data, where available, by the ‘protected characteristics’ of the Equality Act 2010, which are:

- age

- disability

- gender reassignment

- marriage and civil partnership

- pregnancy and maternity

- race

- religion or belief

- sex

- sexual orientation

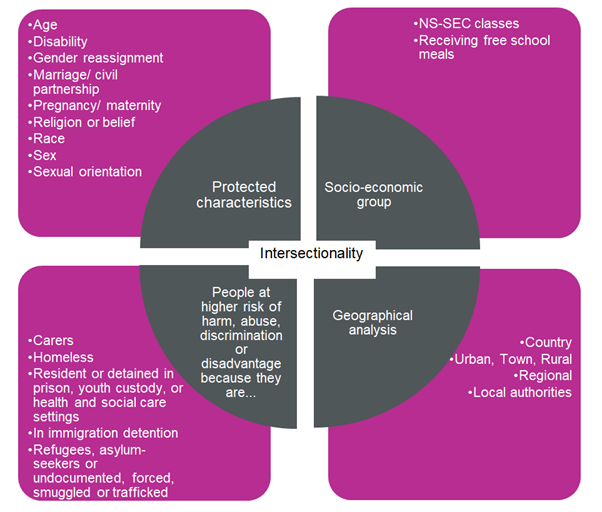

The Measurement Framework aims to monitor systematically the position of certain groups in relation to equality and human rights using disaggregated data. The collection and analysis of evidence has five specific components:

- Protected characteristics

- Socio-economic group

- Geographical analysis

- People at higher risk of harm, abuse, discrimination or disadvantage

- Intersectionality

Diagram showing the five components of evidence collection and analysis

Accessible version of this diagram.

Datasets and variables

Secondary statistical data analysis of survey and administrative data:

The researchers applied nine criteria to secondary statistical data analysis of survey and administrative data collected by public bodies:

- Data should come from official statistics or major academic studies (for example, national surveys and administrative data, such as educational statistics and recorded crime data).

- Data should be available and easily accessible. The process of obtaining data can be lengthy, especially if data are classed as sensitive, for example on sexual identity.

- Analysis of change over time should be possible (so data are collected reasonably frequently), allowing for monitoring; it may be necessary to pool years of data, for example for smaller samples such as when looking at Scotland or Wales, or when looking at some protected groups, such as ethnic minorities.

- Continuity should be provided, not only in the provision of data but in continuity of definitions (for example, of disability) or question wording (if data are survey-based).

- There should be good geographical coverage, preferably including Britain, England, Scotland and Wales, from one source. Failing that, country-specific data that is comparable is preferred, but not always available. In addition, data for the English Regions and/ or disaggregated into the Rural-Urban categories.

- It should be possible to disaggregate according to as many as possible of the nine protected characteristics set out in the Equality Act (age, disability, gender reassignment, race, religion or belief, sex, sexual orientation, pregnancy and maternity, marriage and civil partnership).

- It should be possible to disaggregate disability data into categories of impairment type.

- Although it is not one of the protected characteristics, we also aim to cover socio-economic group/ social class; a crucial characteristic that impacts upon life opportunities across all domains.

- Data should be subject to the standard statistical requirements of accuracy, reliability and validity.

Statistical tests were used to evaluate statistically significant differences for each measure. The tests depended on the form of the measure involved (percentage, mean, median, rate or count) and the underlying form of the dependent variable involved (binary, continuous or integer). Statistical analysis included cross-sectional analysis for two or more time periods, with comparisons between groups in each time period, plus change over time within groups.

Where suitable microdata were available intersectional analysis was carried out. The researchers used regression models for data on protected characteristics, socio-economic group and geographic areas as independent variables, and included selected interaction terms. The analysis was adjusted (where possible and relevant) for any complex survey design. Regression models used for intersectional analysis were developed as follows:

- Analysis for percentages: where the outcome is binary and the measure is a percentage, the data are analysed using a logistic regression model.

- Analysis for means: where the outcome is continuous and the measure is a mean, the analysis is based on a linear regression model instead of a logistic regression model.

- Analysis for medians: Where the outcome is continuous and the measure is a median, for example regarding employee pay, the analysis is based on a median regression model instead of a logistic regression model.

- Analysis for rates: where the outcome is a rate calculated from a number of events (an integer) and a population estimate, standard errors are estimated assuming a Poisson distribution (a discrete probability distribution that expresses the probability of a given number of events occurring in a fixed interval), and a log-linear regression model is used instead of a logistic regression model, with an offset of the natural log of the population to adjust for differences in population sizes.

- Analysis for counts: where the outcome is simply a number of events (an integer), standard errors are estimated assuming a Poisson distribution.

Percentages which are based on an unweighted base of less than 30 are not shown. A sample population in a survey better reflects the whole population. Significance was tested to compare:

- The position of a subgroup with that of the appropriate reference group

- The position of a subgroup in two different years

- Two countries or regions and change over time between two countries or regions.

The Measurement Framework has six domains, which reflect the elements that are important to people and enable them to flourish: Education, Work, Living standards, Health, Justice and personal security, and Participation.

Across the six domains, the researchers used 25 indicators, of which 18 are core indicators and 7 supplementary. For each indicator, the researchers offer a rationale of why it is included and the key structure, process and outcome evidence used.

Across the 25 indicators, there are 50 statistical measures comprising analysis using survey and administrative data. The statistical measures can either be process evidence (if they give an indication of how standards are implemented by the State, for example waiting times for mental health treatment) or outcome evidence (if they give an indication of what people experience, for example self-reported mental health).

The 48 data tables in the Measurement Framework which support the statistical measures in Is Britain Fairer? 2018 are organised across the six domains of:

- education

- health

- justice

- living standards

- participation

- work

Of the 48 measures, 33 use data in the UK Data Service collection:

- Annual Population Survey

- British Election Study

- British Social Attitudes Survey

- Community Life Survey

- Crime Survey for England and Wales (including the British Crime Survey)

- English Housing Survey

- Family Resources Survey

- Health Survey for England

- Households Below Average Income

- National Survey for Wales

- Opinions and Lifestyle Survey

- Scottish Crime and Justice Survey

- Scottish Health Survey

- Scottish Household Survey

- Scottish Social Attitudes Survey

- Taking Part: the National Survey of Culture, Leisure and Sport

- Welsh Health Survey

A more detailed breakdown of datasets by domain is also available.

Gaps in the data

The researchers noted insufficient (or lacking altogether) data for some people sharing certain protected characteristics. They acknowledge that there are far more large-scale Britain-wide data for sex than for any other protected characteristic. The researchers also note “a lack of data for sexual orientation, religion or belief and gender reassignment in particular.” They noted gaps in the data by topic, for example zero hours contracts and types of flexible working and recent national survey data on unfair treatment, bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Across the indicators analysed, the Report provides a comprehensive picture of the issues relating to disability, ethnicity and sex. However, the scarcity of primary quantitative data means that the experiences and outcomes of other groups are less clear.

The researchers noted that in relation to LGBT people, while individual research on specific subjects provides snapshots of evidence of poor outcomes, data is insufficient to determine whether these gaps have improved or deteriorated over the review period. Part of this insufficiency is owing to sensitivities around asking questions on sexual orientation and gender identity, which are necessary to classify respondents within administrative data or surveys.

The EHRC welcomes the UK Government’s National LGBT Survey which sheds more light on these issues, and its commitment in its LGBT action plan, to develop monitoring standards for sexual orientation and gender identity.

Lack of data on religion and belief, and pregnancy and maternity, limits the ability to observe progress over time in many domains. This lack means that the true scale of adverse outcomes and levels of representation in many aspects of life is unclear for people of different religions, for women who are pregnant and for new mothers.

While some evidence is available on experiences of bullying and harassment, particularly of women, the researchers note that this is not the case across all protected characteristics, and not in a systematic way that is robust and longitudinal. An initiative by the EHRC to develop a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination indicates that there are common experiences of prejudice across several protected characteristics.

In order to clarify the extent of these experiences consistently across groups and across time, the EHRC recommends that the Government should put in place a systematic method for examining bullying, harassment, prejudice and discrimination across Britain.

Messages

‘Is Britain Fairer? 2018’ is a ‘state-of-the-nation’ report produced by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) every three years. It covers progress in relation to outcomes in education, health, living standards, justice and security, work and participation in politics and public life. Is Britain Fairer? 2018 makes recommendations to address the key equality and human rights issues identified.

Findings

Education

The research has found that there have been a number of positive developments across education. Attainment at school-leaving age has generally improved. Resources have been targeted on school children from disadvantaged backgrounds, with some success. The proportion of young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) has declined and access to university has widened, particularly for ethnic minorities and those from disadvantaged areas. However, educational inequality persists in Britain. The 2015 review of equality and human rights identified a number of challenges, many of which are found to be just as relevant in 2018:

- large school attainment gaps experienced by Gypsy, Roma and Traveller children, those with special educational needs and children from disadvantaged backgrounds, particularly white boys

- bullying of school children because of their identity

- gender imbalances and stereotyping in the education system

- poor educational outcomes for disabled people, and

- racial inequality in universities, including a large attainment gap between black students and white students.

Health

People with learning disabilities, disabled people, homeless people, migrants, asylum seekers and refugees and Gypsies, Roma and Travellers still experience the most significant barriers to accessing health services. There continue to be stark disparities in the way some protected characteristic groups experience healthcare and this is reflected in their poorer health outcomes.

A lack of data and published evidence continues to limit the ability of health services across the three countries to respond to their needs. People with protected characteristics (other than age or sex) and at-risk groups remain excluded from a range of national and local monitoring data. There is a particular a lack of reliable data collection and published evidence on:

- the LGBT community (particularly the transgender community)

- the health inequalities experienced by Gypsies, Roma and Travellers

- the health and healthcare needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers including immigration detainees

- access to healthcare services for disabled people and homeless people in Wales

- intersectional data for waiting and referral times and access to health services for ‘at-risk’ groups and disabled people with a range of impairment types, and

- the prevalence of illness in English and Welsh prisons, particularly mental health conditions.

Justice

Evidence suggests that some groups, such as disabled people or some people from ethnic minorities, are much less likely to have trust in the criminal justice system. Since 2015, the researchers found a considerable increase in the number of hate crimes, sexual offences and domestic abuse incidents reported to the police. But under-reporting and mis-recording remain key issues.

For sexual and domestic abuse incidents, there is a considerable lack of data on the experiences of disabled survivors, LGBT survivors and survivors from ethnic minorities. Crime Survey for England and Wales evidence suggests that those most at risk are women, disabled people and LGB people. And while conviction rates have remained steady or improved slightly for some offences, conviction rates for rape offences are still 5.6 percentage points lower than they were in 2012/13.

People from ethnic minorities are still over-represented throughout the criminal justice system, but more positive trends are appearing in other areas. For example, there are fewer young people in custody and there has been a decline in the use of police cells as a place of safety. But there is also clear evidence to suggest that conditions in detention have worsened since 2010. Most prisons in England and Wales are overcrowded, while incidents of self-harm in prisons and immigration detention settings have increased in recent years.

Living standards

A continuing increase in homelessness, increased child poverty rates despite decreases in severe material deprivation, and UK-wide social security reforms hitting the poorest hardest, have contributed to an overall fall in living standards in Britain since the last report.

Some groups of people who share protected characteristics and some at risk groups are at higher risk of homelessness, disabled people face a shortage of, and delay in obtaining, accessible and adaptable homes. For Gypsies and Travellers, a more hostile policy environment brought in at the start of the review period is leading to an increase in unauthorised encampments.

One in three children in Britain and half of children from some ethnic minorities are now living in poverty, figures which have increased since the last review. Disabled people, women, and many ethnic minorities are still more likely to live in poverty and experience severe material deprivation. The poverty rate for adults has not changed but the proportion of adults living in severe material deprivation has reduced.

Participation

The researchers found that political and civic participation has opened up for new groups, including 16 and 17 year olds being able to vote in Scottish elections and prisoners released on temporary licence having the ban on voting lifted in England and Wales. Barriers to voting remain for some groups, however, and women remain under-represented among MPs, on public boards and the judiciary despite clear steps being taken by the UK and devolved governments.

The true scale of under-representation for people from ethnic and religious minorities, disabled people and for LGBT people remains unclear because of lack of data.

Access to transport services is in danger of becoming more restricted for some users. Reduced bus services, inconsistency in government efforts to ensure access to transport for disabled users and increasing violent and hate crime on the railways are significant concerns. Similarly access to leisure and cultural services is lower among disabled people, older people, women and lower socio-economic groups, with physical accessibility being key for disabled people.

Work

The researchers note progress in reducing inequalities between people sharing certain protected characteristics in some areas, but not in all. For example, female representation as non-executive directors on FTSE 100 Boards has risen considerably.

The overall employment rate has also increased, although gaps between people sharing certain protected characteristics remain, particularly between disabled and non-disabled people. Similarly, while unemployment rates have fallen for some ethnic groups (although remaining high for Bangladeshi and Pakistani people, substantial gaps between ethnic groups remain. The gender pay gap in hourly earnings remains high, while wide gender pay gaps remain in some occupations and industries, notably the financial sector.

Finally, information is insufficient (or lacking altogether) for some people sharing certain protected characteristics. Generally speaking, there are far more large-scale Britain-wide data for sex than for any other protected characteristic, with a lack of information for sexual orientation, religion or belief and gender reassignment in particular. There are also gaps in evidence by topic, for example zero hours contracts and types of flexible working; “particularly striking is the lack of any recent national survey data on unfair treatment, bullying and harassment in the workplace.”

Findings for policy

The report makes six recommendations to strengthen the legal framework protecting equality and human rights and to fill gaps in evidence. The recommendations identify the organisations considered necessary to take action to address the key equality and human rights issues identified. “Having identified the issues and the changes that need to be made, our own role will be to work with others to help them effect change, and to use our range of powers to influence policy and legislative change, improve compliance with the law and enforce the law when it is breached.”

- In order to use the leverage of public services and resources to address the findings of inequality in this report, governments across Britain and all public bodies should, in performing their Public Sector Equality Duty, set equality objectives or outcomes and publish evidence of action and progress in relation to our key findings that relate to their functions.

- Governments across Britain should review how the Public Sector Equality Duty specific duties could be amended to focus public bodies on taking action to tackle the key challenges in this report.

- To ensure that public bodies work together to reduce the inequalities linked to socio-economic disadvantage, the socio-economic duty should be brought into force in England and Wales by the UK and the Welsh Governments as a matter of urgency.

- Governments across Britain should implement all provisions of the Equality Act 2010 outstanding in their nation, within their remit. This includes the duty to make reasonable adjustments to common parts of rented residential properties, the requirement for political parties to report on diversity of candidates, and the explicit prohibition of caste discrimination.

- The UK Government should make a clear commitment to remaining permanently within the European Convention on Human Rights, and should publish action plans for implementing UN recommendations on human rights.

- The UK Government should ensure that equality and human rights protections are safeguarded and enhanced during the Brexit process and beyond, and should legislate to replace gaps in rights in domestic law resulting from the loss of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Impact

The UK’s most senior judge has condemned the effects of government austerity on families, women and minorities, in an unusual political attack. Lady Hale, president of the Supreme Court, said cost-cutting had worsened the struggle of some families to find enough money for daily life and had caused problems in the legal system:

“The problem that we have in the courts is that it is quite obvious – indeed it is officially conceded – that many of the recent changes to the benefits system impact more harshly on women, children and disabled people than they do on other groups: for example, the recent report from the Equality and Human Rights Commission, Is Britain Fairer?, states that ‘UK-wide reforms to social security and taxes since 2010 are having a disproportionate impact on the poorest in society and particularly affecting women, disabled people, ethnic minorities and lone parents’.”

The EHRC launched the ‘Is Wales Fairer?’ companion report at an event at the Welsh Assembly attended by the UN Special Rapporteur for Extreme Poverty.

Conclusion

‘Is Britain Fairer? 2018’ concludes that there are more women, black people and Pakistanis in employment, and more women in higher pay occupations; the gender pay gap is decreasing. The report concludes that there is, however still a lot more to do to ensure everyone is free from discrimination and can enjoy their basic human rights:

- The picture is still bleak for the living standards of Britain’s most at-risk and ‘forgotten’ groups of people, who are in danger of becoming stuck in their current situation for years to come

- Black African, Bangladeshi and Pakistani people are still the most likely to live in poverty and deprivation, and – given the damaging effects of poverty on education, work and health – families can become locked into disadvantage for generations

- Ethnic minorities are more at risk of becoming homeless, have poorer access to healthcare and higher rates of infant mortality, and some groups have lower trust in the criminal justice system

- Gypsy, Roma and Travellers face multiple disadvantages across different areas of life. They achieve below-average results at school, experience difficulties accessing healthcare, worse health, and often have low standards of housing

- The level of hate crime, sexual violence and domestic abuse is concerning

- Higher rates of domestic abuse and sexual assault experienced by disabled people, LGBT people and women are also of concern

- There is a marked backwards move in justice and personal security

- The disability pay gap persists, with disabled people earning less per hour on average than non-disabled people

- Poverty has changed little and for children it has increased.

“This report makes it clear that as a nation we face a defining moment: Across many areas of life there are still too many who are losing out and who feel forgotten or left behind. Unless we take action, the disadvantages that many people face risk becoming entrenched for generations to come.”

David Isaac CBE, EHRC Chair

Publications

Reports

Video

British Sign Language (BSL) summary of ‘Is Britain Fairer? 2018’ report (28 minutes)