About the research

People in higher professional and managerial occupations tend to command large incomes, exercise substantial power in their workplaces and pass significant advantages on to their children. Daniel Laurison and Sam Friedman assert that class analysis needs an approach which registers class destinations more effectively. Drawing on data from the ONS Labour Force Survey (LFS), the UK’s largest employment survey, the researchers demonstrated that a powerful ‘class pay gap’ exists in the UK’s elite occupations and in ‘the professions’ more broadly. The researchers identified the LFS as a “gold standard, nationally representative source” upon which to draw.

The researchers found that in higher managerial and professional occupations, people from privileged backgrounds in elite occupations earn on average 16% more than colleagues from working-class backgrounds . Significantly, they found that this gap persists even when comparing individuals who have the same educational attainment, occupational role and level of experience.

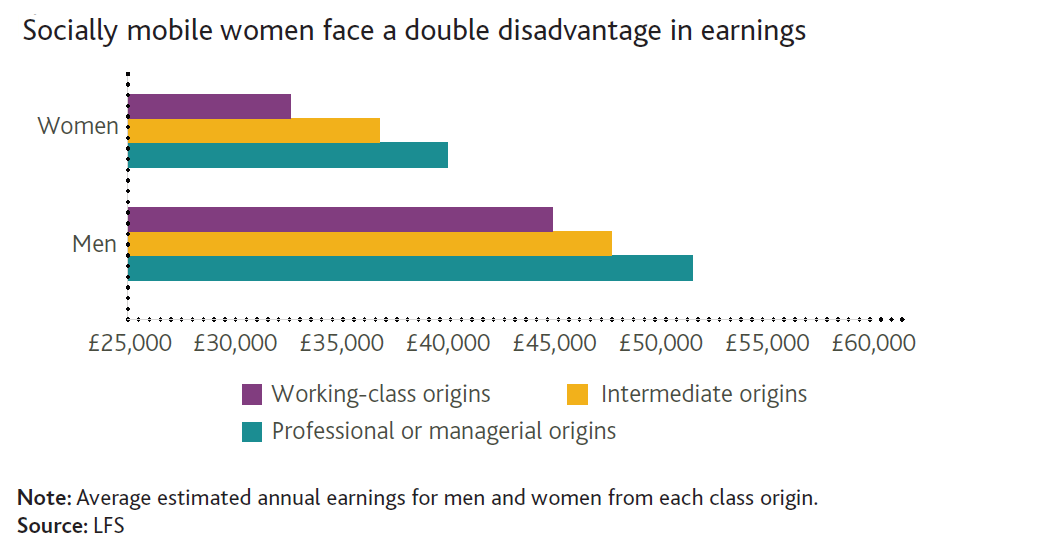

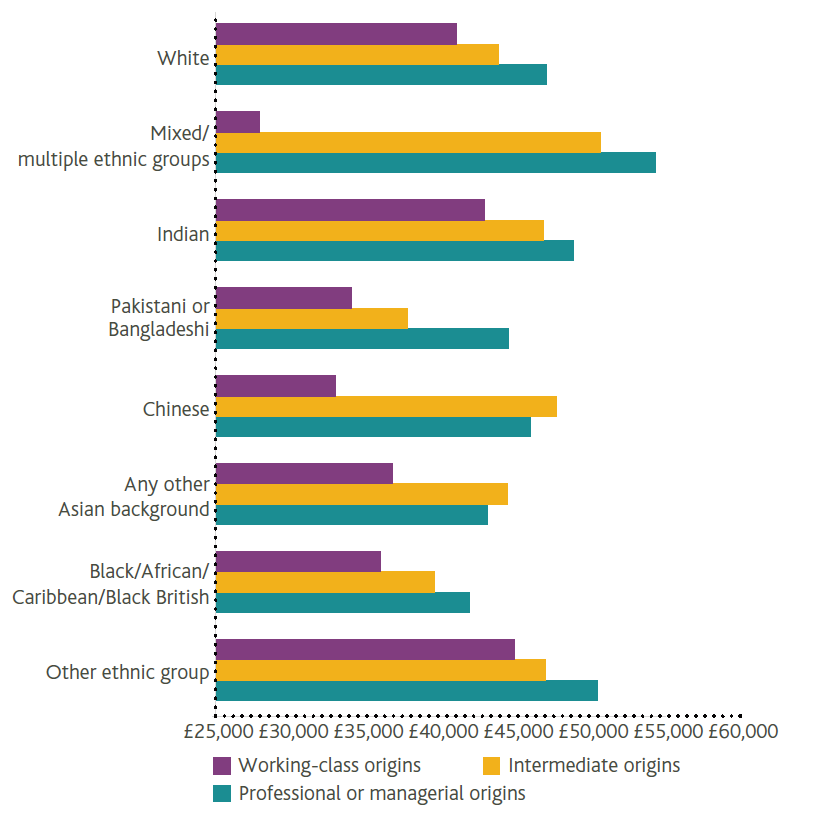

The researchers showed how the class ceiling intersects with the glass ceiling, indicating that women, many groups of ethnic minorities and people with disabilities are significantly under-represented in top jobs and experience relatively reduced incomes. The research also showed how earnings inequality is concentrated in certain occupations – such as finance and accountancy – and in certain places – such as Central London.

Funding for the research

The class ceiling project is funded by Dr Sam Friedman ESRC Future Research Leaders Grant (ES/N001184/1).

Headline message

The research focuses on the many ways in which privilege affects career outcomes and finds that the upwardly mobile face a powerful and previously unrecognised ‘class pay gap’ within the UK’s elite occupations. It identifies the channels through which class inequalities are reproduced and identifies steps to support meaningful change.

Methodology

The researchers analysed the Labour Force Survey (LFS) to provide the first large-scale and representative study of social mobility into and within the UK’s higher professional and managerial occupations. Find out more about the Labour Force Survey.

The LFS is a random sample, nationally representative survey; it contains detailed and accurate measures of individual earnings and employment context; and significantly for the researchers, it includes variables that enabled analysis of three key areas considered to affect earnings:

- measures of educational attainment, and specifically whether a respondent has attended university

- both educational attainment and other key human capital measures such as job tenure, job training and health

- measures of an individual’s work context that are known to be associated with distinct occupational advantages, such as working in London, in large firms and in the private versus public sector.

The data contain large sample sizes and detailed social origin data, providing an unprecedented opportunity to understand the relative exclusivity of different high-status professions in the UK.

Specifically, the researchers linked the data from July 2013 through to July 2016, giving access to over 18,000 people working in elite jobs and offering an unprecedented opportunity to shine a light on the openness of the upper echelons of British society. Their aim was to understand whether mobility is more common into some sectors or occupations than others.

The researchers advocated a Bourdieusian approach as the theoretical basis for their research (Pierre Bourdieu 1987) where: “…our class background is defined by our parents’ stocks of three primary forms of capital:

- economic capital (wealth and income)

- cultural capital (educational credentials and the possession of legitimate knowledge, skills and tastes); and

- social capital (valuable social connections and friendships).”

Forms which, “…not only structure the overarching conditions of our childhoods, we also tend to inherit them … upper-middle-class parents are able to directly pass on to their children both financial assets and valuable social contacts, both of which go on to confer advantage in fairly self-evident ways.”

The researchers continued: “The material affluence of the educated upper-middle classes, Bourdieu argued, affords them a certain distance from economic necessity that is then strongly reflected in the way they socialise their children. In particular, they inculcate a certain ‘habitus’ – a set of dispositions that organise how their children understand and relate to the world around them.”

Datasets and variables

Analysis was undertaken of respondents in the 63 occupations that make up Class 1 of the Government’s National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC) – defined as the UK’s elite. The researchers then looked at the class origins of people in these occupations, and most importantly how their income varies according to their class background (using NS-SEC classes 1-8).

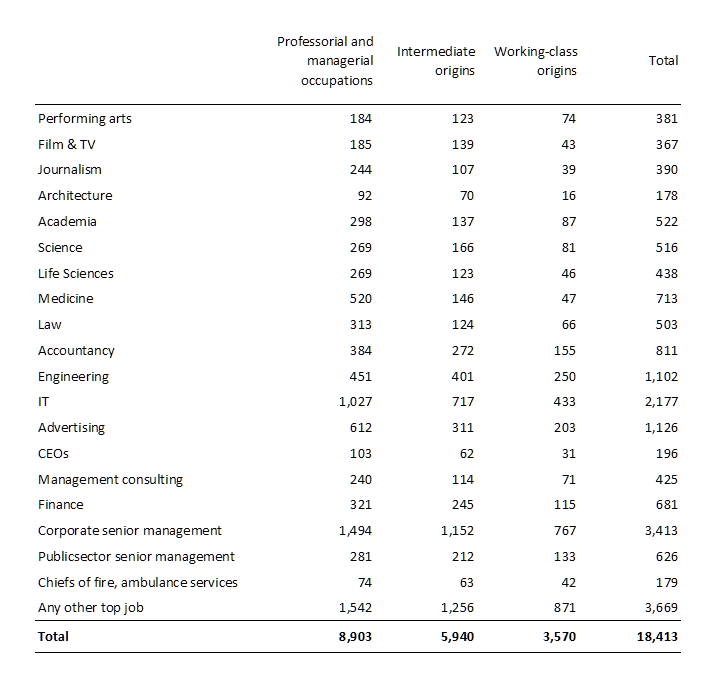

Focusing on respondents who have a particular occupational destination in an ‘elite occupation’, the researchers defined ‘elite’ in terms of all higher professional and managerial (NS-SEC 1) occupations plus a set of cultural and creative jobs. Together these occupations constituted a sample of 18,413 respondents in the linked waves of the LFS. The researchers distinguished 19 individual professions within this group.

Number of LFS respondents in each elite occupation by origin:

Click on figure for larger version.

The goal was to create occupational groupings with broadly similar training, skills and work contexts, while also having a sufficiently large sample within each group to allow for meaningful inference: Not every person included in the analyses of the full ‘elite’ destination is within one of these 19 occupational groups; 2,177 have an NS-SEC 1 categorisation but no specific occupation recorded, and 1,492 are in occupations that have sample sizes too small to analyse individually and that could not be sensibly grouped with other elite occupations.

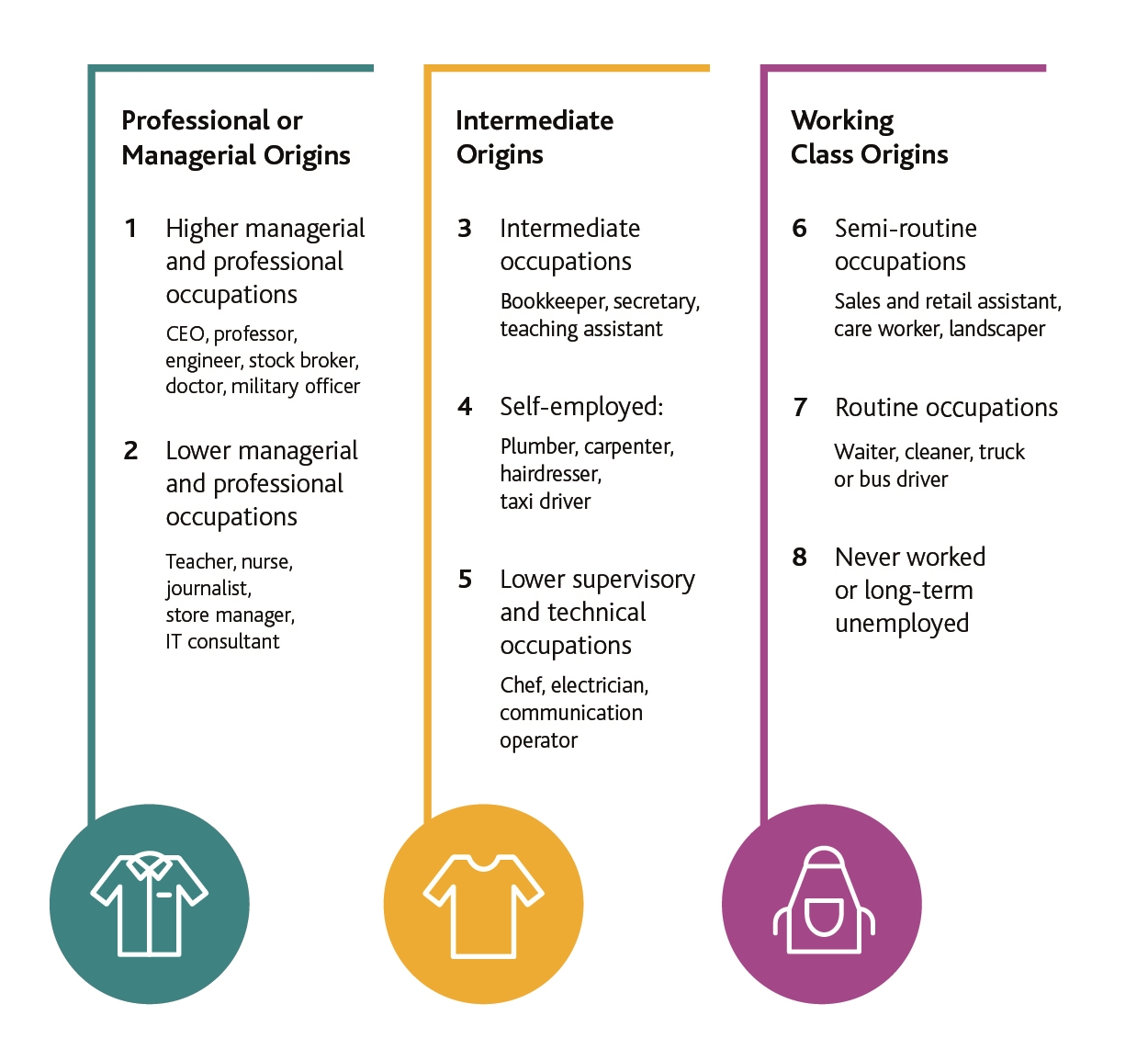

The researchers referred to the LFS question that asks respondents, ‘When you were 14 what was the occupation of the main income-earner in your household?’ (Notably, in over 80% of cases, this means the occupation of the father.) Based on answers to this question people’s origins were grouped into the seven classes of NS-SEC; those with no income-earning family member are coded into an eighth category for the long-term unemployed. Figure 1.1 highlights examples of occupations in each NS-SEC origin class.

How the researchers measured social mobility into elite occupations using the NS-SEC origin classes:

The researchers restricted the sample to those aged 69 or younger to minimise the effects of retirement. They removed all individuals under age 23 or in full-time education from the analyses; including the widest reasonable age range to focus on the composition of professional and managerial jobs, rather than mobility chances by origin.

Messages

The research focuses on the many ways in which privilege affects career outcomes and finds that the upwardly mobile face a powerful and

previously unrecognised ‘class pay gap’ within the UK’s elite occupations. It identifies the channels through which class inequalities are

reproduced and identifies steps to support meaningful change.

Findings

People’s origins and destinations

Drawing on the addition of the socio-economic background variable to the LFS in 2014 about the job of the main income-earning parent when a subject was 14, the researchers examined mobility inflow rates among higher professional and managerial occupations.

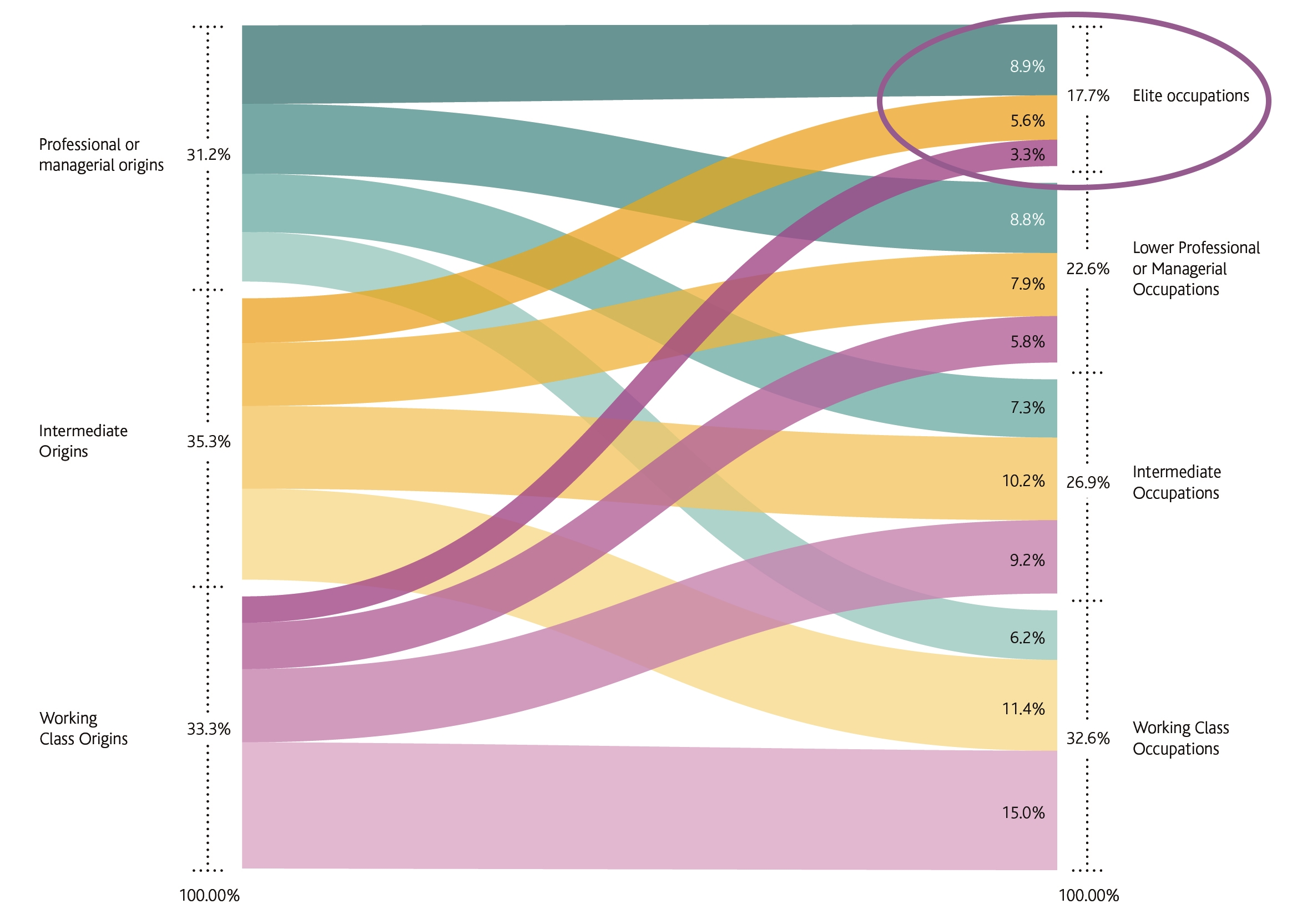

The flows from left to right represent people from each class origin who moved into each class destination and the thickness of each line shows the proportion who take each possible path:

Click on figure for larger version.

The figure shows that the thickest lines – the most common paths, denote people staying in roughly the same class position they started in, with only about 10% of people from working class backgrounds (3.3% of people overall) traversing the steepest mobility path.

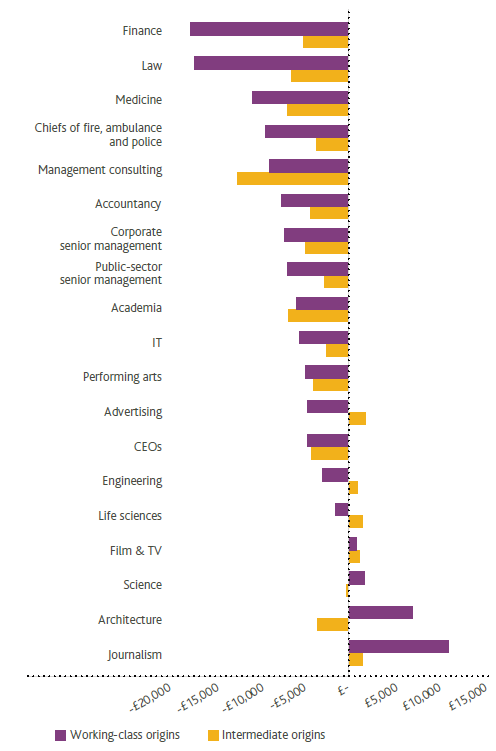

The researchers found that people in elite occupations whose parents were employed in semi-routine and routine working-class jobs earn on average £6,400 a year less than their colleagues from higher professional and managerial backgrounds:

The Class Pay Gap: People from privileged origins earn about £6400 more each year.

Moreover, the researchers found that people from NS-SEC 1 backgrounds are nearly twice as common in NS-SEC 1 as in the general population (26.6% vs 14.1%), while the relationship for people with parents who worked in routine employment is reversed: they constitute 18.3% of the population but only 9.5% of NS-SEC 1. It is also possible to detect a pattern of distinct micro-class reproduction, where children with parents in medicine and law are 21 and 18 times (respectively) more common in these fields than in the population as a whole. While higher managers earn more, the higher professions remain significantly more elitist in terms of restricting access for those from working class backgrounds.

The figure demonstrates the biggest pay gaps:

Upwardly mobile women face a significant “double disadvantage” based on both class origin and gender. They earn on average £7,500 less per year than privileged-origin women, who in turn earn £11,500 less than privileged origin men:

The researchers found that there are not enough ethnic minorities in NS-SEC 1 occupations (only 300 with earnings data), however, for much statistical power: only the coefficient for long range upwardly mobile ethnic minorities is statistically significant, demonstrating a “double disadvantage” for many racial-ethnic groups:

The researchers note that it is important to acknowledge the limitations of their analysis. While the Labour Force Survey certainly provides the most detailed understanding of mobility into NS-SEC 1 to-date, the sample size for many individual occupations is small. Moreover, the results can only provide a snapshot of social mobility.

Findings for policy

Any such future work should focus on the numerous resources associated with class origin such as parental income and wealth, powerful social networks, elite private school or university attendance, and cultural tastes or practices with widely shared legitimacy.

The researchers interviewed employees from different backgrounds at different grades to understand the class pay gap in four professions:

- Multinational accountancy firm

- Television broadcaster

- Architecture firm

- Self-employed actors

They found that those from working class backgrounds drop off sharply as grades increase, noting a vertical sorting into a ceiling effect, excepting in architecture. The researchers noted four main drivers emerge from these case studies:

- Financial safety net bank of mum and dad

- Enables more risk-taking in their career

- Filtering out of the most competitive areas of professions for more stable but less lucrative roles

- Sponsorships operating beneath formal process in a form of patronage

The researchers noted that of most pivotal importance was the ability to fit in in terms of apparel, understanding and exemplifying behavioural codes and access to a package of self-presentation including language and etiquette, equaling embodied cultural capital. A tendency was observed for this embodied cultural capital to be important in particular kinds of elite professions.

The researchers propose ten policy recommendations to address the class ceiling in the UK’s elite professions:

- Measure and monitor class background

At present there is little consensus across sectors about the measurement and monitoring of class or socio-economic background. Many organisations still don’t collect data in this area and, among those that do, a range of different measures are used.

- Find out whether your organisation has a class ceiling

Effective measurement has two dimensions. Organisations of course need to understand the overall class composition of their workforce. But they also need to go further and investigate whether they too have a class ceiling.

- Start a conversation about talent

One of the most significant drivers of the class ceiling is how talent and ‘merit’ are defined and rewarded within organisations. It is critical that employers interrogate how ‘merit’ is recognised within their organisation, and to what extent it can be reliably connected to demonstrable output or performance.

- Take intersectionality seriously

Equality and diversity provision within organisations is very often organised one-dimensionally along a single axis of social inequality, such as gender or ethnicity. Yet people’s work lives are better understood as being shaped by many axes of inequality that often work together and influence one another, or create distinct types of disadvantage that are experienced in different ways.

- Publish social mobility data

Positive change with respect to social mobility requires collective responsibility and collaborative action across sectors. To achieve this, individual organisations need to be bold and transparent about the issues they face by publishing data regarding the class backgrounds of all staff and senior leaders in particular.

- Ban unpaid and unadvertised internships

One of the clearest drivers of the class ceiling is the way in which those from privileged backgrounds use the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ to help them establish their career. The researchers advocate a four-week legal limit on all internships; the use of apprenticeship levy funding to generate quality placements; and the publishing of accessible national guidance on the rights of interns.

- Senior champions are necessary but not sufficient

If organisations are going to take social mobility seriously there needs to be meaningful buy-in from senior management. In the best examples observed, a very senior individual acts as a visible champion for forwarding the agenda.

- Formalise the informal

The research shows that across elite occupations a culture of informal sponsorship exists. Here senior staff, often operating outside of formal processes, are able to fast-track the careers of junior staff whom, crucially, they are initially drawn to on the basis of cultural similarity. Formalise and democratise sponsorship opportunities.

- Support those who want it

People from working-class backgrounds often self-eliminate from pushing forward in their careers, or sort into less prestigious areas: rejecting expectations to assimilate, battling feelings of ‘otherness’, or negotiating low-level but constant microaggressions in the workplace. It is important that organisations consult with staff from disadvantaged backgrounds about how to best support them.

- Lobby for legal protection

The Equality Act 2010 ensured legal protections for a range of minority groups but did not include class or socio-economic background. What is less known is that the Act actually contains a section entitled the ‘Socioeconomic Duty’, which requires government and all public bodies to have due regard for ‘reducing the inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage’. Bringing this section into effect would provide a clear mandate for making class background a protected characteristic.

Why does this matter for sociology?

Dominant approaches to social mobility fail to capture the long shadow of class origins and the way merit is defined and rewarded in elite occupations is implicated in rates of mobility.

Thinking about privilege as a prevailing wind also has ramifications that extend beyond elite occupations. “In all of these domains, the issue is, is that when the following wind of privilege is misread as merit, the resulting inequalities are legitimised. This perception of merit leads those who have been fortunate to believe they’ve earned it on their own and those who have been less fortunate to blame themselves.”

“By shedding light on the ways in which merit is at best an insufficient explanation for career success at the top, it will be possible to raise wider questions about the legitimacy of an economic system that too often allocates profoundly unequal rewards based on the accident of social origin.”

Conclusion

The Class Ceiling project proposes a fundamentally new way of conducting social mobility research. While ‘fair access’ to elite occupations is invariably presented as the most important indicator of a just society, this presentation masks a much longer shadow which class origins cast on occupational trajectories. By uncovering and exploring these hidden barriers, the project not only aids understanding of how class inequalities are reproduced but also aims to inform policy initiatives aimed at breaking down elitism and encouraging true equality of opportunity.

Impact

State of the Nation 2018-19: Social Mobility in Great Britain: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attach ment_data/file/798404/SMC_State_of_the_Nation_Report_2018-19.pdf

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Social Mobility: https://www.suttontrust.com/policy/all-party-parliamentary-group-on-social-mobility/

Within Britain’s elite occupations, the advantages of class are still mistaken for talent: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/07/the-classpay-gap-why-it-pays-to-be-privileged

The Performers’ Alliance All Party Parliamentary Group is looking into social mobility in the creative sector: https://www.musiciansunion.org.uk/Home/News/2019/Mar/Breaking-the-Class-Ceiling

The ‘Hidden Mechanisms’ that help those born rich to excel in elite jobs: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/02/class-ceiling-l aurison-friedman-elite-jobs/582175/

Publications

The Class Ceiling – Why it Pays to be Privileged by Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison, Policy Press: https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/the-class-ceiling

Project website: https://www.classceiling.org/

Video of LSE ‘Class Ceiling’ event: https://richmedia.lse.ac.uk/publiclecturesandevents/20190128_1830_%20theClassCeiling.mp4

Breaking the Class Ceiling, BBC Radio 4: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0002rjj

The ‘Hidden Mechanisms’ That Help Those Born Rich to Excel in Elite Jobs, The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/02/class-ceiling-laurison-friedman-elite-jobs/582175/

The class pay gap: why it pays to be privileged, The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/07/the-class-pay-gap-why-it-pays-to-be-privileged

Introducing the ‘class’ ceiling, LSE British Politics and Policy blog https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/introducing-the-class-ceiling/

Thinking Allowed: The Class Ceiling, BBC Radio 4: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000281t